The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has high hopes. A young country with an ancient history, it aspires to be recognised for its strategic location, its educated but cost-effective labour force and an industrious work ethic. And it might be succeeding. Société Générale, T-Mobile, Swedmilk and Porsche are among the international companies that have assessed the challenges and grasped them.

That others will make the same choice is almost guaranteed – in October, the World Bank’s Doing Business 2008 ranked the country as the fourth-best reformatory state among 178, and praised the country’s new government, led by prime minister Nikola Gruevski, for its reform efforts. And in November, the World Bank’s vote of confidence was corroborated by a European Commission progress report which lauded the EU candidate’s efforts to axe unnecessary regulation, improve education and sustain macroeconomic stability.

Advertisement

This is not to say that Macedonia has not got work to do – corruption and unemployment are two elements of everyday life and the economy that ministers must continue to take steps to reduce. Wider geopolitical issues are outside of its gift to influence, and present political and regional difficulties that any government might find challenging, but the government believes that the internal situation is such that potential regional unrest should not disrupt its own economy unduly.

Investment search

With a population of just 2.1 million and an area of about 26,000 square kilometres Macedonia is not large. Nor is it resource rich or a major exporter of raw materials. Thus it has made sense for the government to take the steps it has to attract strategic investors from Europe and beyond.

As part of its own strategy, the country’s Skopje-based inward investment agency has honed in on 12 industry sectors where it believes Macedonia has some significant value to add, and markets a packet of incentives that may serve to take some of the edge off the uncertainty of investing in a country that has traditionally been eclipsed by larger neighbours. Among these, it cites duty free market access to about 650 million people (the inhabitants of the EU, eastern and southern Europe and Turkey), competitive low salaries in the region of €370 per month, a low corporate tax rate (already reduced from 15% to 12% in 2007, but to be whittled down to a competitive 10% in 2008) and a state-of-the-art infrastructure as being some of the most important.

Of more ambiguous merit is the availability of labour. More than one in three of the population of working age is without a job, although a sizeable proportion of those are almost certainly employed in the ‘grey economy’; keeping labour costs down for investors perhaps but creating social strains and putting pressure on overburdened state institutions.

On its way to EU membership

In its latest progress report on European enlargement, the European Commission outlined the economic strides the country has made, noting that it “registered a markedly accelerated economic growth” between 2006 and 2007, that “macroeconomic stability has been maintained” and that it has “advanced in and further moved towards establishing a functioning market economy”.

Advertisement

In addition, it says, the country has made great efforts to improve transport links in the country to leverage on its crossroads position in the Balkans (the republic borders Greece, Albania and Serbia).

But the report also criticises Macedonian institutions. It says that poor relations within the political establishment and elite, including the non-participation of one of the country’s largest parties, corruption and “institutional weaknesses” hamper the economy, while the judiciary continues to be a “bottleneck” and regulatory and supervisory authorities “sometimes lack the independence and resources to fulfil their function”.

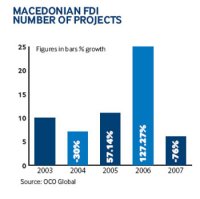

Given Macedonia’s history since the break-up of Yugoslavia, it would be surprising if institutional weaknesses had been removed and political learning curves ascended overnight. And it seems to be sending the right signals. In 2006, FDI stood at about $350m – not a substantial figure relative to larger economies but more than trebling the previous year’s equivalent of $100m. Between 2002 and 2006, by sector, infrastructure (electricity gas and water) stole the show, representing about 35% of the total, with manufacturing and transport/communication runners up at 18% and 14% respectively.

Nerves of steel

In recent years especially, Macedonia has shown that it can attract a diverse portfolio of investors. Arguably one of the most significant of these was Mittal Steel’s acquisition of facilities (an 800,000-ton hot strip mill and a 750,000-ton cold rolling mill) from Balkan Steel in

2004. While part of Yugoslavia before 1991, Macedonia possessed a thriving steel manufacturing industry with which it supplied the rest of the country. Mittal’s acquisition of Balkan Steel’s facilities was seen as reviving what the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) describes as “a crucial part of the economy which would otherwise have lain stagnant”, and which now employs more than 1000 workers.

One year on from the acquisition, Mittal borrowed about €25m from the EBRD to finance an energy efficiency programme and to promote “regional integration” with the company’s other plants in the region, notably in Romania and Bosnia Herzegovina.

Tax incentives

More recently still, a significant footprint is being made by US autoparts manufacturer Johnson Controls, which is constructing a $40m manufacturing facility on the outskirts of Skopje. The Milwaukee-based company is taking advantage of incentives offered by a Technological Industrial Development Zone on the outskirts of Skopje, including a 10-year holiday from corporate profits tax and property tax, freedom from VAT and excise duties for the same period, and special arrangements with central government to minimise bureaucracy.

Other ‘hot-off-the-press’ investments in Macedonia include a decision by Porsche Bank, part of Porsche Holdings, to begin car leasing operations in the country in March 2008, and Swedish dairy plant company Swedmilk. The CEO of Swedmilk’s Macedonian subsidiary recently told other potential investors at an investment conference that the Macedonian experience was comparable to investing in the Baltic countries at the beginning of the 1990s.

A lot can happen in a decade and a half in the Balkans, as recent history has shown, and while Macedonia clearly has a good news story to tell, regional rumblings will undoubtedly deter some that would otherwise take the risk. But for those taking the long view, the pluses are many, and extend not only to the prospect of membership within the larger European fold, but to its dynamism, talented labour pool and diversity.