After a rollercoaster ride, inward investment into Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia is juddering to a halt. All three nations understand that investment is important to economic recovery and that innovation and skills development are key.

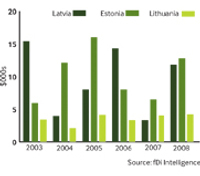

Although outsiders tend to lump the states together as a single entity, the relationship between each is competitive, not least in the sphere of FDI. Nonetheless, they share some common characteristics. Ralff Dakters of the Latvian Investment and Development Agency says that the “strategic marker” for the region was 2004, during which all three states acceded to the EU, putting clear blue water between the Baltic states and the former Soviet Union. It marked, he says, “a dramatic increase in FDI”, which peaked in 2006 and 2007.

Advertisement

In Latvia, the government has kept investment flow records since 1995, and its own sectoral breakdown for investment into the state between 1995 and the third quarter of 2008 is as follows: more than one-quarter of investment has been into the financial services and financial intermediary sector, with 14% in the retail sector, 13% in real estate, 12% into the services sector, 8% into logistics and transport and a further 8% into manufacturing.

Services and manufacturing Mr Dakters says that 67% of Latvian GDP is generated by the service industries, and only 9% is from manufacturing. He also highlights the importance of foreign capital flows into the economy. “A mere 13% of the workforce is employed by companies owned by foreign capital – wholly owned subsidies, for example – but nonetheless, this sector is responsible for producing 66% of GDP, which shows quite how profitable, disproportionately even, these companies are – and important for the economy.”

Compounding his observation is the fact that exports account for some 52% of the country’s output. “This, and the fact that our negative trade balance is to some extent offset by FDI, is the reason we have to pay attention to foreign investors.”

Mr Dakters says the agency’s policy is to distinguish between those areas in which it is happy for the free market to take the lead, and other, more strategic spheres of economic activity. “For example, there has not been a single investment into manufacturing which hasn’t seen a significant involvement from us. But we are trying to only be involved in those areas where it actually matters,” he says.

He acknowledges that “globally, there is less investment. Period. And we aren’t likely to be an exception to that. There will be less investment in Latvia during 2009 than there was in 2006 or 2007, but we do hope at least to realise the same levels as in 2004 and 2005.

Advertisement

“The danger lies in the fact that more than half of the investment currently lies in those areas such as financial services and real estate development, which are largely dependent on economic activity for their own stimulus. We are seeing a number of long-term investors, including some multinationals, who are hanging back, trying to gauge what demand is going to be looking like in three to five years.”

Quality over quantity

Mr Dakters makes the point that in the long term, Latvia is less concerned about the quantity of investment than it is about the quality, and he and his colleagues are looking at how best they can attract high-value investment into sectors such as IT, call centres, R&D and pharmaceuticals. The balance has shifted perceptibly; the timber sector traditionally dominated, but this formerly top export has been nudged out of pole position by engineered metal products.

High standards of education and training are key to this. “Also,” says Mr Dakters, “being in the centre of the Baltic region is important – not least because we are a mere hop away from Scandinavia.”

Scandinavia is of enormous importance to the Baltic countries. Sweden is the largest investor, followed by Denmark, Germany and Finland, and Mr Dakters says he is hopeful that a large Scandinavian company, a manufacturer of modular housing, will soon make the decision to invest in the creation of a factory producing housing components for its own market.

Lithuania’s struggles

Meanwhile, in Lithuania, Mantas Nocius, managing director of the Lithuanian Development Agency, reports that even before the credit crunch, Lithuania “had not been doing so well in terms of FDI”, which, he says, has since 2004 been supplanted by the availability of “cheap and easy credit”. Lithuanian FDI is typically about €3000 per capita, with the Latvian figure a little higher and Estonia at a remarkable €8000 per capita.

Mr Nocius says that the global economic situation – “the new situation” – reinforces the need for that position to alter. The time for cheap loans is well and truly gone. But he adds that not all Lithuanian businesses are in hock; he describes those with spare cash as being “extremely conservative” and not using their capital – with both positive and negative effects: good that the country can demonstrate

a nationwide instinct for prudence, but a restraint on economic recovery.

In the short to mid-term, Mr Nocius foresees three potential avenues of foreign investment into the country. In the first place, there are those companies which have sufficient liquidity to seek interesting and value-driven opportunities around the world. He cites MOG, a US technology company which includes medical appliances within its portfolio and has recently bought a Vilnius company for an undisclosed but not insubstantial sum. The company is considering building a laboratory in Vilnius, encouraged by the high technical expertise of its employees, cheaper labour costs and EU support.

Production centres are another opportunity, he says, as manufacturers search for cheaper, but highly skilled destinations. He cites the UK company RGE Injection Moulding, which has a 7.9 million-square-metre plant in Lithuania producing parts for companies including IKEA and Indesit.

Mr Nocius identifies potential in the Lithuanian service centre sector. In June 2008, US systems integration and outsourcing company CSC established an 80-employee presence in the country, which has since grown to 300 employees. He says: “We had a Norwegian debt collection agency come here recently. They needed Norwegian speakers to service their domestic customers so they set up intensive Norwegian language centres to train employees, and within a remarkably short period of time they had a Norwegian-speaking workforce at a considerably lower cost than they would have had if they’d hired domestically.”

Key skills

Gert Stahl of Enterprise Estonia would agree with Mr Nocius that technical and language skills will prove critical to the future success of these small states. Mr Stahl says that it is commonplace in Estonia, which is adept in information communications technology (ICT), for graduates to speak three or four languages in addition to their native Estonian. German is still widely spoken, as is Russian (the first language of one-third of the population), alongside English, Finnish and Swedish. Estonia’s post-Soviet youth quickly became IT literate early in the 1990s and the country could boast a communications infrastructure envied by many Western countries within a few years of independence. In 1995, when a mere 20 internet-based banks existed worldwide, three of these were based in Estonia. Mr Stahl says: “If I tell you that FDI accounts for 75% of our GDP then that gives you some kind of idea as to how important it is to our country.”

The Estonian approach is maturing. After the initial wave of investment, largely into the ICT sector, the country welcomed other companies: engineering company ABB, for example, which, Mr Stahl says, has only ever reinvested profits from its Estonian operations. After EU accession in 2004, German and Dutch companies began to recognise the opportunities so investments were further diversified into areas such as biotech, materials technology and environmental technology. The plan nationally is to leverage on Estonia’s existing technical expertise to create a value-added platform for long-term investors. And, says Mr Stahl, to make sure that companies already in the country – including Arcelor Mittal, Skype (an Estonian company now owned by eBay), Microsoft and Sun Microsystems – feel appreciated with consultations and dialogue.

Intelligent approach

Enterprise Estonia is also committed to taking an intelligent approach to attracting new investment, not only announcing itself to be open for business but targeting specific companies through its liaison offices abroad. Mr Stahl says that although the world may not be universally familiar with Estonia, an increasing proportion of its population is not only well travelled, but has received its higher education entirely outside of the country.

Small nations such as the Baltic states, which regard each other as rivals, will face challenging times as investment slows down across the board. But they have already demonstrated the extent of their versatility through the extent to which they have adapted to post-Soviet independence and by their participation in the European and international community. As and when the global economy begins to sprout green shoots, the Baltic states could well find themselves once again ahead of the curve.