A van carrying around a colourful billboard burst into London’s streets just a couple of weeks after the Brexit referendum. “Dear start-ups, keep calm and move to Berlin,” it read.

As journalists scrambled to trace the German FDP political party that funded the stunt, advertisements of post-Brexit investment opportunities in European cities such as Vienna sprang up in the British press, and the telephones of some of London’s fastest growing companies started ringing.

Advertisement

“Ireland, Switzerland, others reaching out and tempting @TransferWise to start/move operations there,” Taavet Hinrikus, CEO and co-founder of London-based fintech sensation TransferWise, tweeted on July 4.

Investment scramble

The June 23 referendum – in which the country voted by a majority of 52% to 48% to leave the EU – marked a seismic shift in the UK’s international trade policy. Now that the problem-strewn relationship with the EU appears to be coming to an end, the country must decide upon its place in the global trade arena. Where this place will be is anybody’s guess. With official negotiations with Brussels not expected to start before 2017, and slated to last for up to two years, investors face a protracted period of uncertainty. Former European partners have already made a move to intercept this uncertainty and tap into any opportunity that may come their way. Their calls are not falling on deaf ears.

“Competition between states is good :),” Mr Hinrikus also tweeted.

Downing Street is not dithering. Brexit has left an unusual – albeit momentary – void in British laws and policies, but it gives the new government, led by Theresa May, plenty of room to manoeuvre to fill that void and, eventually, fend off European competition regarding investment by pulling the fiscal lever and strengthening ties with partners beyond Europe. A weaker currency is already playing into its hands, as foreign bargain-hunters bid for discounted British assets.

The Brexit FDI threat

Advertisement

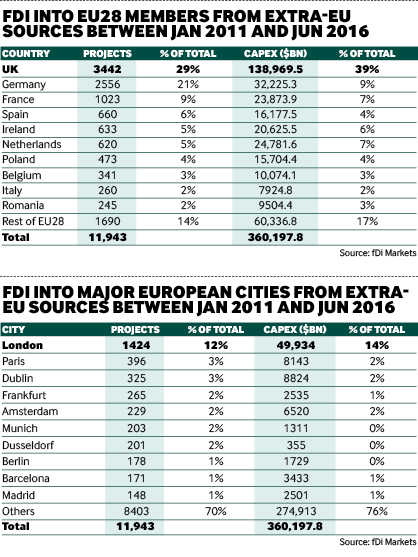

The perspective of losing free access to the European market is a dire one for a number of key export-oriented industries operating in the UK that flourished under the country’s EU membership. So-called passporting rights propelled the City of London to new heights by granting its products and services access to the whole continent. The city attracted nearly 12% of all projects into the EU over the past five years, three times as much as Paris or Frankfurt, according to figures from greenfield investment monitor fDi Markets.

The future of these passporting rights now hangs in the balance and will be at the core of the Brexit negotiations slated to start at the beginning of 2017. Meanwhile, financial groups are working out their contingency plans, with heavyweights such as JPMorgan, HSBC and Morgan Stanley reportedly considering relocating some of their London workforce should the UK lose its current passporting rights.

“Nobody knows what the rules of the game tomorrow will be,” says Muriel Pénicaud, managing director of national investment promotion agency Business France. “But some financial companies are clearly looking for opportunities to have a second base on the continent. It’s a competition among a few cities, and Paris is certainly one of those.”

Eyeing London's jewels

To incentivise the post-Brexit decision-making of these companies, France announced generous tax breaks for executive returnees. Meanwhile, cities with a vibrant start-up scene, such as Berlin, are eyeing London’s fintech companies.

“We are dealing with enquiries from fintech companies [located in the UK] trying to figure out whether they can do better in other European countries,” says Stefan Franzke, CEO of public-private investment promotion agency (IPA) Berlin Partner. Most of the companies sounding him out had concerns about the future of their international workforce, he adds. They are, it seems, waiting to see how the UK government reshapes the country’s immigration policy.

Goods exporters are feeling the chill too, particularly in the automotive sector. Auto producers active in the UK export 75% of their annual 1.6 million vehicle production, with half of their overseas shipping bound to the EU. Any possible trade tariff between the EU and the UK would squeeze out their already tight margins.

Under a worst-case scenario, where trade between the UK and the EU is regulated by a standard World Trade Organization tariff of 10%, mid-market foreign car manufacturers such as Honda, General Motors and Nissan may see the competitiveness of their British facilities plummet and eventually assess other locations for the production of new models, according to reports footed by market intelligence firms PA Consulting and LMC Automotive.

“It’s too early to tell what Nissan’s response is going to be,” says Guy Currey, director of Invest North East England. The Japanese car manufacturer has invested a total of £3.7bn ($4.94bn) in the UK's largest car factory, which is located in Sunderland in north-eastern England. “It is playing its cards very close to its chest,” he adds.

Appeal still strong

Although Brexit brings along unprecedented uncertainty, the UK's FDI appeal will not be tarnished overnight. The country attracted almost one-third of all FDI projects to the EU between 2011 and May 2016, the highest of any member, according to figures from fDi Markets. Domestic growth potential and the availability of skilled talent rank just after the country’s access to regional markets as the main determinants for foreign investment, fDi Markets figures show. Brexit will likely affect both, at least in the short term, with economic growth now expected to slow down and the future of the citizenship status of foreign talent still hanging in the balance. Nonetheless, a number of investors have already reasserted the soundness of the country’s business proposition.

“It is hard to find a better place to do science than at Cambridge,” Pascal Soriot, CEO of Anglo-Sweden pharma giant AstraZeneca, said during a conference call on July 29, when he announced a £330m investment in R&D operations in the city. Competitor GlaxoSmithKline has also teamed up with Verily, the life sciences arm of Google, to develop a new £540m research centre in Scotland, and will also power up its production base with an extra £275m investment.

“It’s not all doom and gloom as we had thought, there are people willing to invest,” says Willie Young, a councillor in Aberdeen, a Scottish city 100 kilometres away one of the production facility that GlaxoSmithKline will upgrade. “The question now is what kind of return will people get from their money.”

Unique proposition

Come what may, the return that investors get for their money will no longer depend on Brussels, and this alone makes Brexit worthwhile, according to many of the 'Leave' campaigners.

“Anything that enables the UK to provide a unique selling point to the world is ultimately to our advantage,” says Rupert Gather, executive chairman at InvestUK, a private firm assisting foreign investors considering an investment in the UK.

Without wasting time, the freshly appointed chancellor of the exchequer, Phillip Hammond, has already hinted at possible cuts in corporate tax and VAT rates to offset any possible impact from higher trade tariffs. At the same time, his cabinet peer Liam Fox, minister for international trade, made clear his desire to pursue trade deals across the globe in autonomy from Brussels, provided that the UK leaves the European customs union.

With this in mind, the US and Japan, historically the largest non-EU sources of FDI into the UK, and China, whose commercial ties with the country have been soaring during the reign of former prime minister David Cameron, are the natural priorities. A weak sterling creates extra room for capital investment from overseas.

“The UK has just become 10% cheaper,” says Tim Newns, chief executive of Invest in Manchester, as the pound stabilised to about 1.32 to the dollar in the Brexit aftermath, prompting a fresh wave of crossborder M&A, such as the proposed £24.3bn acquisition of British smartphone chip designer Arm by Japanese conglomerate Softbank.

However, the UK remains a net importer of goods and services and any gain from the weak sterling is likely to be offset by higher import costs in the medium term. At the same time, Ms May and Mr Fox have sent out conflicting signals about the country’s future outside the customs union. The prime minister also raised eyebrows among cabinet members when she delayed a £18bn nuclear project by French company EDF on the grounds of concerns about the role of Chinese capital in the overall development.

Stumbling onwards

These early disagreements within Ms May’s government hint at a lack of unity over the form that a post-Brexit UK should take. The quick leadership turnaround that fast-tracked Ms May to becoming prime minister left no void of power, but it came at the cost of having a cabinet that is still working out its Brexit strategy. As it figures it out, economic indicators are heading in a worrying direction prompting the Bank of England to cut interest rates to 0.25% on August 4. Investment is expected to follow suit.

“Our underlying premise is that greenfield FDI into the UK is inevitably going to decline,” a report by FDI consultancy firm Wavteq said in July.

The London School of Economics estimates that Brexit will lead to a 22% decrease of FDI over the next decade. Local investment promotion agencies will have to recalibrate their promotion strategies as the post-Brexit reality settles in by focusing on the sectors and markets with the highest potential, putting more resources into supporting existing foreign investors, and considering expanding their mandate to encompass M&A and new forms of investment, according to Wavteq’s report.

“It’s either eat or be eaten,” Aberdeen councillor Mr Young concludes. Time will tell whether Brexit turns the UK into the predator or the prey.