UK prime minister Boris Johnson declared in his New Year’s message that leaving the EU on January 31 will provide certainty and “help unleash a pent-up tidal wave of investment” in the UK. Mr Johnson is confident that his agenda will spread “opportunity to every corner” of the country.

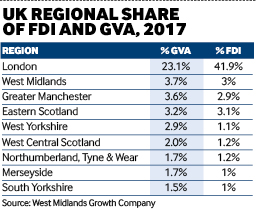

But if history is any guide, pent-up investment from abroad is unlikely to spread evenly across the UK. London has long been the epicentre of the UK economy, generating more than 23.1% of the UK’s gross value added (GVA) in 2017 – a GDP measure adjusted for taxes and subsidies – while attracting 37.8% of the UK’s inbound greenfield FDI projects, according to greenfield investment monitor fDi Markets.

Advertisement

Indeed, the capital is the only region and city to attract more of the UK’s greenfield or headline FDI than its share of GVA or GDP. For example, the northern city of Leeds contributed 4.1% to the UK’s GDP in 2014, but received only 0.77% of its greenfield FDI. Meanwhile, fDi Markets data shows that south-east England – the region in which London is located – has accounted for a whopping 47% of the UK’s greenfield foreign investment since 2003.

“Over recent years there have been a lot of complaints that the FDI that comes to the UK just goes to London,” says Paul Swinney, director of policy and research at the Centre for Cities, a non-profit research group focused on the UK economy. “Other parts of the country [say] there is a London bias, and that the authorities don’t promote the rest of the UK as well

“The hard reality is that different places are offering benefits to different extents. London is offering both access to a deep pool of skilled workers and access to other skilled businesses, which appeals to investors coming to the UK. From a business perspective it makes more sense to invest in London than elsewhere [for ‘knowledge-based’ sectors].”

Regional powerhouses

While London and the south-east have attracted the lion’s share of greenfield investment projects in the UK, advanced manufacturing is strong outside the capital.

There have been 466 greenfield projects announced in manufacturing across just three UK regions (Scotland, the West Midlands and north-west England) outside London since 2009, accounting for almost 40% of the total number of projects, according to fDi Markets. Greater London attracted just 14 manufacturing projects over that period.

Advertisement

Scotland has welcomed 274 inward manufacturing projects since 2003, 89% more than the average of 145 across all regions of the UK. The West Midlands, the north-west, north-east and Wales also received a higher than average number of manufacturing projects.

A study of UK regions’ attractiveness as locations to set up an automotive component manufacturing plant, undertaken by investment destination comparison tool fDi Benchmark, ranked the West Midlands as the most attractive, followed by the east of England and north-west England.

However, the regions need strategic policy change to better diversify foreign investment beyond manufacturing, according to Mr Swinney. The principal challenge facing many cities outside London, Edinburgh and Bristol – such as Birmingham, Liverpool and to a lesser extent Manchester – is that these places are not offering to a sufficient degree the skilled workers that businesses are looking for, or a fast enough evolution of city centre space, he adds.

“Successful cities have a real diversity of businesses within them. London is not just a finance city,” says Mr Swinney. “[Moreover] the UK’s productivity problem is not to do with the south-east – which has one of the highest in Europe – but to do with other parts of the country. When you dig into the stats, it is the underperformance of those parts of the country that is the main reason for the UK’s malaise in productivity.”

Storm clouds

The dangers of manufacturing dependency have been cast into stark relief by Brexit. The IHS Markit/CIPS manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI), a monthly survey of purchasing managers at private manufacturing firms, revealed the sharpest deterioration in output in more than seven years in December 2019.

The PMI, which gives a picture of whether the manufacturing industry is growing or contracting, showed that the majority of businesses indicated deteriorating activity for eight consecutive months. In a Bank of England survey of almost 3000 chief financial officers in December 2019, 53% of companies reported that Brexit was one of their top three sources of uncertainty.

Entrepreneur Elon Musk, for example, picked Berlin for Tesla’s European gigafactory due to such uncertainty. Meanwhile, Brexit has led some foreign companies to relocate their UK operations. Since the referendum result in 2016, there have been 80 relocation projects from the UK, according to fDi Markets. This compares with just nine relocations in the 13 years to May 2016.

Despite being the third largest benefactor in terms of greenfield investment into manufacturing, the West Midlands had the largest proportion of leave voters, with 59.3% of the 2.96 million residents that voted in the region electing to cease being a member of the EU. A 2017 academic study showed that the regions that voted strongly for leave tended to be those same regions with greatest levels of dependency on EU markets for their local economic development.

Historical neglect?

Brexit has had an equally deleterious impact on the UK government’s regional policy.

“[Over the past few years] the UK government has had no vision for cities outside London,” says professor Michael Parkinson, associate pro vice-chancellor for civic engagement at the University of Liverpool. “It is less interested in the devolution agenda, and much more wedded to London, devoting all its energy to Brexit. Plus, with austerity, there’s no money for devolution.”

What, then, can Mr Johnson’s new government do to narrow the gap between London and the UK provinces? There has been too much focus on transport over skills policy, contends Mr Swinney.

“We should think less about links between cities, and more about better transport links within cities outside London,” he says. “Nonetheless, the real challenge in these cities remains skills. Public and private providers of further education need to coordinate their activities, as with the Skills Compact in [the US city of] Boston.”

Mr Swinney is also sceptical of tax cuts and, in particular, the notion of more free zones across the UK, arguing that tax cuts tend to attract ‘low-skilled’ businesses and that London is evidence of how companies are willing to pay premium for high skills.

Some suggest the UK government would do well to prioritise education policy outside south-east England, believing investors will follow. Regardless of these potential solutions, Brexit looks set to pose a series of challenges for Mr Johnson's new government. Huge promises have been made to the UK's cities outside of London, and the success or failure of his premiership may well be decided by what he delivers in these areas.