Abi Woldemeskel lived in London in the 1980s when heartbreaking images of starving Ethiopian children were broadcast around the world, launching massive international aid efforts. Charity volunteers collected donations, yet few of those he asked knew where Ethiopia was, he says.

The difficulty for Mr Woldemeskel and his colleagues at the Ethiopian Investment Agency (EIA) is that knowledge of the country is sparse and perceptions remain rooted in those images from two decades ago. The task of the agency, which was established in 1992 after Ethiopia emerged from decades under a dictatorship that had nationalised most industry, is to convince foreign investors to take a serious look at a country that has been known mostly for famine and war.

Advertisement

“We are trying our best to encourage private sector investment, especially FDI,” says Mr Woldemeskel, director-general of the EIA. Back in London in June on a mission to meet with successful British investment promotion agencies and engage potential investors, he told fDi of the “enormous” opportunities that ongoing privatisation presents for foreign investors in the construction, hotel, tourism, manufacturing and textile sectors.

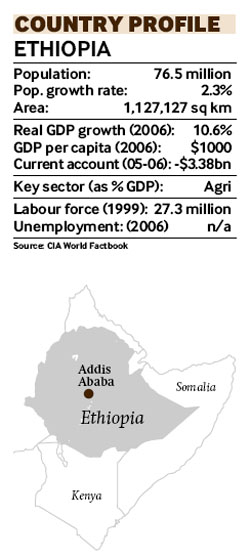

To entice investors, the government has worked to reduce bureaucracy and make it easier to do business, he says. “It takes two days to set up a business now. Ethiopia has signed several investment protection treaties and double taxation treaties and is a member of MIGA; the law gives equal treatment to domestic and foreign businesses. And, despite the turmoil of the 1980s, the macroeconomy is stable, with GDP growth of more than 10%.

“We have established a situation in which investors can feel at home. The government is committed to encouraging the private sector.”

Agriculture is “the pillar on which our economy stands”, says Mr Woldemeskel. Ethiopia’s 18 climatic zones are suitable for growing a wide range of products, including food crops, flowers, coffee and tea. The country is the biggest livestock producer in Africa, with 41 million heads of cattle, 25 million sheep and 23 million goats. Commercial processing of oil seeds is another area of interest. “Our climate is an asset and lends itself to almost all agricultural activities as well as tourism,” he says.

There are 2300 hectares of available land suitable for growing cotton, which, combined with low labour costs, presents an opportunity for textile factories to locate there and set up efficient and short supply chains, adds Mr Woldemeskel. Likewise for leather goods, given the large cattle population.

The government hopes that tourism will become a pillar of the economy. It is seeking investment in hotels, restaurants and tours, and encouraging construction of grade-one roads, buildings and infrastructure. As the seat of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the Africa Union, Ethiopia’s capital city, Addis Ababa, is a perennial host for regional and international summits and its five-star Sheraton hotel bustles with diplomatic traffic.

Advertisement

“Ethiopia is the hub of Africa,” says Mr Woldemeskel. “We also have one of the best airlines in Africa, with regular flights to London, Washington, Asia, the Middle East and elsewhere. Ethiopia is totally different to what it was 15 years ago.”