The noise of F-16 fighter jets breaking the sound barrier over the Bosphorus on July 15 of this year remains a vivid memory for the residents of Istanbul. It signalled that the Turkey of long-standing president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, although repeatedly hit by external terrorist threats over the past couple of years, could be even be haunted anew by the threat of a military coup from within, as had often been the case in the pre-Erdogan era.

Foreign investors will hardly forget July 15 either. Turkey is a key piece in the Middle East’s already fragile geopolitical puzzle, and has accumulated billions in investment over the past 20 years thanks to its burgeoning economy. The coup eventually failed, and the situation has stabilised since that night, but today’s Turkey is not business as usual.

Advertisement

The government declared a three-month state of emergency in the aftermath of the coup (now extended for another three months), which paved the way for a massive crackdown on alleged members of the movement headed by self-exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen, whom the government considers the ultimate mastermind of the coup. The state of emergency also gave Mr Erdogan the power to bypass parliament and push through economic reforms aimed at reassuring investors and shoring up economic growth amid the current turbulence.

However, the international community is growing increasingly uneasy with Turkey’s current state and Erdogan’s methods. The country lost its investment rating, pushing down the Turkish lira, which fell to new lows in the currency market. The economy is slowing down and foreign investment is following suit. Although numerous investors have reiterated their commitment to the country, levels of FDI are falling. The fundamentals of the Turkish economy may be untouched, but growing political and security risks have now spilled over, hindering the economic cycle as a whole.

Economic slowdown

“Headline-wise clearly the news story remains a mixed picture to negative,” deputy prime minister Mehmet Şimşek told fDi at the World Investment Conference organised by the World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (Waipa) in Istanbul in October. “But I would argue that we will show that the Turkish democracy is stronger [now], and that the political environment is now more conducive to reform despite the [current] noise. Of course there will be economic fallout, and that is already reflected that in our medium-term economic forecasts. That’s likely to be limited and short-lived. It doesn’t change the fundamentals.”

Earlier in October, the government reviewed downwards to 3.2%, well below a previous target of 4.5% and the 4% achieved in 2015. The growth estimate for 2017 was also lowered to 4.4%, from 5%.

From a more regional perspective, Turkey’s growth rate is twice that of the eurozone, thanks to its dynamic export-oriented manufacturing sector and deep consumer base. However, a number of key sectors are taking a beating. Among those, tourism certainly stands out. The sector alone contributed 12.9% of the national GDP and 8.3% of total employment in 2015, according to figures from the World Travel & Tourism Council. Merchants on Istanbul’s main shopping high street Istiklal have been reportedly suffering from reduced business for months, and they mirror the overall sentiment of tourism-related businesses across the country. The total number of tourists visiting Turkey fell to 16.7 million in the first eight months of 2016, down from 24.2 million in the same period of 2015. The failed coup caused concerns among tourists, some of whom had already been put off visiting the country by the terrorist attacks on Istanbul, Ankara and the country’s south-east in the past 18 months.

Advertisement

Fading investment

Despite the current political and economic woes, foreign investors have not fled the country altogether.

In fact, “various international investors operating in Turkey […] reaffirmed their support for the democratically elected government, institutions, the rule of law, and the Turkish people,” Arda Ermut, president of the country’s Investment Support and Promotion Agency (ISPAT) fold fDi. “Drawing attention to the importance of a functioning democracy, CEOs of these companies emphasised the significance of an uninterrupted flow of trade and investment. Furthermore plenty of companies announced new investments in Turkey.” Mr Ermut highlighted the $526m Turkish fund set up by Dubai-based Abraaj Capital, a growing global force in the private equity arena.

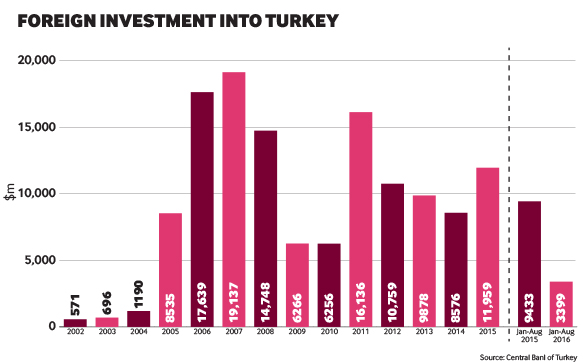

However, the latest developments are inevitably haffecting investment figures. Overall FDI has been plummeting throughout 2016, as the failed coup further imperilled a business sentiment already depressed by the political instability the country experienced in 2015, when a first round of general elections in June 2015 failed to produce a majority in parliament, forcing new elections a few months later. FDI inflows did not exceed $3,399m in the first eight months of the year, from $9,433m in the same period of 2015, according to figures from the Turkey’s Central Bank. Productive investment into greenfield projects is also experiencing a sharp downfall. Total greenfield FDI was $3,428m in the year to date, down by 24% from a year earlier, according to figures from FT data service fDi Markets.

“Companies are continuing their investment programmes, but the frequency is lower,” Sabit Tapan, country manager for executive search firm Pedersen & Partners, fold fDi. “Before we were talking of investments in the order of billions, now in the millions, if that. It’s not about managing growth any more, but about handling the crisis.”

Foreign executives are also growing increasingly hesitant to move to Turkey.

“The impact on expats living in Turkey has been low, they can better understand what is happening and are living with that,” said Mr Tapan. “On the other hand, foreigners are increasingly hesitant about Turkey and many of them don’t want to move to Turkey at all.”

Cross-border M&A

If productive investment is falling, the depreciation of the Turkish lira is somehow shoring up cross-border financial investment. Foreign bargain-hunters are scouring the market for opportunities at discounted prices because the lira depreciated by about 5% against the dollar since the beginning of the year and now trades at historical lows of around 3.06 to the dollar as of October 19.

“To be honest I was expecting business to be really bad [after the failed coup], because it was a safety issue at the beginning,” says Eren Kursun, partner at Backer&McKenzie/Esin Attorney Partnership, one of the main legal firms specialising in M&A in Turkey.

“For the few first days it was dead silent, because nobody cared about business. Things are still slow, we are no longer in the blossoming, flourishing environment, but not that bad after all. […] If you are buying Turkish businesses with US dollars, this is a good environment. Besides, the Turkish market has been a sellers’ market for many years, but in time like this sellers become more realistic with evaluations.”

Mr Kursun adds that only one in 15 cross-border M&A deals he is working was halted when the promoting foreign investor pulled the plug in the aftermath of the coup.

Total cross-border M&A deals amounted to $6.66bn in the year to October 19, up by 10% from a year earlier, according to Bloomberg figures. However, the market has showed little sign of activity since July 15, with total cross-border M&A deals falling to $204.7mn, down by 86.4% year on year. Turkey saw its investment grade rating scrapped by Moody’s in September, when the credit rating agency mentioned, among other reasons, “the erosion of Turkey’s institutional strength, which was evident prior to the failed coup attempt but which the event may exacerbate”. Standard & Poor’s had already downgraded the country’s rating in July immediately after the coup.

Nevertheless, representatives of the local business community believe the argument of weakening institutions and rule of law has been somehow overstated by external observers.

“We lived through an extraordinary situation with this coup attempt, and that’s why extraordinary steps should be taken,” Ömer Cihad Vardan, head of the Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEIK), one of the country’s leading business organisations, told fDi, referring to the ongoing purge of people allegedly affiliated to the Gülen movement, which led to the dismissal or suspension of about 100,000 people working in the public sector, as well as the arrest of more than 32,000 people, including 127 journalists, according to estimates from independent sources. If some local and international observers labelled it a massive witch-hunt engineered by Mr Erdogan to get rid of any internal opposition, Mr Vardan sees it differently.

“Those responsible for the coup should pay,” he says. “We have no concerns about the rule of law in Turkey. We have a democratic pedigree rooted in our past, and we are just waiting this operation to end.”

Extraordinary reforms

The government is now playing the reform card to restart the investment cycle. A new tax law that seeks to improve the investment climate in Turkey by amending certain regulations came into force in August, and another on project-based investment incentives package that will provide financial support with lower interest rates for “strategic” projects came into force the following month.

However, the country will need more than reforms to put itself back on track. Growing political, institutional and economic woes are a troublesome combination for foreign investors to swallow. The same is true for those many Turkish citizens not in denial.

“Everyday there is some new development and for the first time in my life I don’t know what is going to happen one day, one month or one year from now,” one Turkish businesswoman who preferred to remain anonymous told fDi.

The answer will eventually lie in the developments coming up in the next few months, which will show whether Mr Erdogan is really building a stable edifice, or another house of cards.