Last year was a bumpy ride for the world economy and foreign investment was not immune from the potholes and speed bumps that faced the global financial markets. As with almost everything pre-crisis, the foreign investment landscape had been booming. Since 2003, FDI across the globe – both greenfield and mergers and acquisitions (M&As) – had been on a steady upswing, with a sharp increase in investments during the second quarter of 2008.

Between 2005 and 2007 M&As accelerated past greenfield capital expenditure, in late 2008 fDi Intelligence forecast that there would be a decline of 14% to 15% in greenfield FDI projects, later revised to 20% once the severity of the recession was clear (the actual decline was 18%). Yet since 2008, the value of M&A deals fell much faster and greenfield investments again became the key driver in global FDI. The good news is that as foreign investments are closely related to both GDP in general and GDP growth – with the IMF projecting 3.1% GDP growth worldwide in 2010, which is up from -1.1% in 2009 – FDI should begin to get back on track. Numbers from fDi Markets indicate that foreign investment projects are beginning to increase, rising from 1290 projects globally in January 2009 to 1381 projects per month by October.

Advertisement

“FDI was very much a victim of the crisis,” says Karl Sauvant, head of the Vale Columbia Centre on Sustainable International Investment. “And that has all sorts of implications because after all, investment is the basis for economic growth and development.”

Regional variation

So which countries and regions have been the winners and losers? Although there has been a greenfield capital expenditure decline in every region in the world, the hardest hit has been the ‘rest of Europe’ region – eastern Europe being the worst affected, with a drop of 40%. The region encompassing central and eastern Europe, the Balkans,

CIS countries and Russia saw a drop from more than $2bn in the first three quarters of 2008 to about $1.3bn in the same period of 2009. Africa saw a similar fall in investment. The country that experienced the biggest decline overall was Romania – where FDI fell by a whopping 60% – while Russia and the United Arab Emirates experienced declines of between 55% and 60%.

According to research by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), FDI flows to countries in eastern Europe and the CIS dropped by 39% last year. Unctad reported that in south-east Europe, the “near exhaustion” of major privatisation projects and intrinsic weaknesses of national economies – along with the recession – were the chief contributing factors, while CIS countries were affected by a drop in demand for major commodities from countries abundant with natural resources. Africa, meanwhile, saw several crossborder M&A deals failing to reach completion which, together with the absence of any large one-off investments, contributed to a serious decline in the value of M&A investments across the continent.

Advertisement

Bearing the brunt

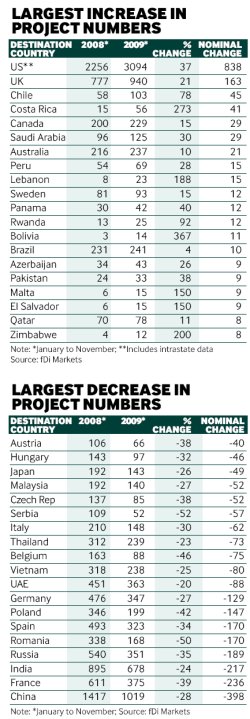

According to data from fDi Markets that compares performance from 2008 through to November 2009, the biggest losers in terms of a decrease in inbound greenfield projects during this period were Serbia (-52%), Romania (-50%), Belgium (-46%) and Poland (-42%), while China saw the worst nominal drop of all countries, with project numbers falling from 1417 in 2008 to 1019 last year. However, countries such as the US, the UK, Canada, Ireland and Hong Kong were all able to maintain or increase their project levels, partially because they all specialise in sectors and activities that are resilient to the recession and are also the lowest-risk locations. Countries such as Bolivia (367%), Costa Rica (273%), Lebanon (188%) and Rwanda (92%, see story, page 70) all saw major increases in FDI projects in 2009, bucking the global trend, while the US topped the league tables with 838 new projects.

“In past recessions, there was a lag of about a year or two before there was an effect on foreign investment flows, but this time the decline was almost instantaneous,” says Mr Sauvant. “There are a couple of interesting things associated with this particular crisis. One is that M&As are the key vehicle to entering foreign markets and, of course, the recession dampened demand. Another reason is that multinational companies are increasingly integrated with international production networks and these networks, in turn, can serve as a conduit to pass on shocks so the integrated nature means the shocks can be transmitted more rapidly,” he adds.

Certain sectors felt those shocks more than others. According to fDi Markets, through the third quarter of 2009 the impact of the recession was very industry specific, so while there were declines of projects in construction (55%), chemicals (45%) and manufacturing (35%), resilient areas included the retail trade, energy, life sciences and renewables; and growing business activities included retail, call centres, logistics and R&D. “All those sensitive to business cycles, such as manufacturing and automobiles, were affected,” says Masataka Fujita, an investment analysis at Unctad. “But certain sectors were

not affected and some even rose, such as food and agriculture, goods and services, and pharmaceuticals.”

Future of FDI Overall, the outlook for FDI in 2010 looks positive. According to Unctad, there are several macroeconomic indicators that imply the general climate for foreign investments is slowly regaining momentum.

From a multinational perspective, profits have been on the increase worldwide since the second quarter of 2009 and this could lead companies to revaluate their investment plans for 2010, giving rise to increasing foreign investment flows. However, as the economic growth and recovery are still in the early, delicate stages – enhanced in large part by stimulus packages put together by G-20 economies – FDI recovery may remain modest compared with the boom years.

“I do not expect a substantial increase of FDI flows this year because companies still have to re-leverage, demand may not pick up that much and therefore I would not expect a major resumption of growth,” says Mr Sauvant. “However, in the longer term, I would certainly expect that FDI flows will return and grow beyond the previous peak of $2000bn, unless – and this is an important condition – the regulatory environment changes drastically,” he adds.

Tax moves

Some countries – the UK being among the worst offenders – have made greedy corporate tax grabs during the recession and several companies such as McDonald’s, Regus and Informa have moved their headquarters out of the UK to avoid a tax rate of up to 50%. But Mr Fujita does not expect this to happen in most other locales and predicts that only certain industries will be affected.

“For certain sectors, some companies are quite reactive – such as financial companies, which are relatively easy to relocate – compared with something like a manufacturing company, where once established it is hard to move,” he says. “Most countries have a very low tax rate, therefore I do not think there is much overall tax differential so it will not affect most companies.” A trend which may continue after the recession is the consolidation of companies through such factors as outsourcing, which will help sectors such as business process outsourcing to grow. Foreign investments could even prove to be part of the solution to the crisis.

“It is encouraging that FDI flows are less volatile when compared to other investment flows, which is important because it stabilises a bit even if it declines,” says Mr Sauvant. “And general investment, including FDI, contributes to a resumption of growth and that is something which I think countries are aware of.”