Nordic real estate companies have been blessed with strong growth and returns since the financial crisis. Indices such as the Carnegie Real Estate index have doubled in value in the past five years. But can this performance last? House prices, which have been rising over the past six years, especially in Sweden, fell by about 10% between September 2017 and February 2018. Is this having an impact on the commercial real estate sector? What are the key drivers of real estate performance?

“Normally, I expect 10% total performance per year on my portfolio, but the average in the past five years has been 20% per year,” says Jonas Andersson, lead portfolio manager of Alfred Berg’s Fastighetsfond Norden, a fund investing in Nordic property stocks. “I target more than 10% going forward for 2018 and 2019.”

Advertisement

Mr Andersson calculates the “more than 10%” on a company’s net asset value level as a cashflow yield of 6% plus a 2% value growth at an average leverage level of 55%, which doubles the impact of the property value increase. “But that is based on a 2% value growth – I assume values to grow even more,” he says.

Knock-on effects

But how do these expectations square with the fall in house prices, especially in Sweden?

“There are quite important differences between the drivers of the housing market and the commercial real estate side,” says Anna Breman, chief economist at Swedbank. “The correction in the housing market on the non-commercial side has really been a side-effect of regulatory changes, higher levels of construction and hence more supply in the market, and it is mainly driven by the largest cities.”

Ms Breman adds that in the commercial real estate market, low interest rates, global growth in general and domestic economic expansion, as well as a growing business sector, play more of a role when analysing the performance of the real estate segment. Additionally, there have been no significant regulatory pushes or increased supply that could affect the market negatively.

Not just real estate

Advertisement

Yet, despite the historically strong performance of real estate equities in the Nordic region, many listed companies are currently trading below net asset value, according to Max Barclay, head of Sweden-based full-service property house Newsec Advisory.

As Pangea Property Partners’ real estate-specific indices show, the Nordic retail sector has been hit particularly hard in 2018. In the first 16 weeks of the year, the company’s PREX Retail index is 8.2% lower, while construction (-0.9%) and mixed real estate (-0.1%) have also underperformed, pushing the overall PREX Property index down 0.5% in 2018 to date.

Company and sector selection is, therefore, crucial for investors. Alfred Berg’s Mr Andersson, for example, is underweight on retail-exposed real estate companies and favours those renting out offices, a sector in which the Pangea index

has increased by 1.2% in 2018 to date.

“Stockholm is super hot. Here we have seen the highest percentage increase for office rents,” he says. “There has been a shortage in new office space, while demand is increasing, so rent levels are booming.”

Vacancy rates in the Stockholm office sector are very low at 2.5%, compared with 5.4% in Oslo, 6.8% in Copenhagen and 6.9% in Helsinki, according to Swedbank research. The bank predicts that office rental growth in Stockholm will slow down.

Sweden’s surge

From a macro-economic perspective, the recent rapid increase in the Swedish population from 9 million to 10 million in 2017 and expectations of 11 million inhabitants by 2025, will also have an impact on the real estate industry, according to Ms Breman.

“Given that you have this high population growth in Sweden, there is a lot of need for investment into real estate that is focusing on the public sector: schools, daycares and elderly care,” she says. “These demographic factors are supporting the commercial property market.”

According to research from Pangea, the outlook is positive for both offices and logistics, slightly positive for the public sector and neutral for the residential and hotel real estate sectors, while the retail outlook is slightly negative, although there is a “large difference” between prime and secondary retail.

“The retail real estate market has been punished far too much by stories of mall closures in the US, which are not comparable with Europe,” says Marcel Kokkeel, chief executive at Finland-headquartered retail real estate development company Citycon. “In the US, you can copy any store and you can build it anywhere. At Citycon, we are investing in urban shopping centres, which are uniquely integrated with public transport and offer community services such as libraries or walk-in medical services.”

Focus on the core

Citycon, which started out as a Finland-focused business, has over the past five years trebled its equity and broadened its exposure geographically to become a pan-Nordic company. It now looks to divest its assets in smaller cities to focus on the Nordic capitals.

“We now have relevant size, which allows us to focus on investing in the assets we have, to make them better and have them work better for the community,” says Mr Kokkeel.

Companies such as mixed real estate businesses Kungsleden and Castellum are following similar strategies, which see them sell assets outside their key focus areas while further consolidating their portfolios.

The fourth largest Nordic property company, Hemfosa Fastigheter, meanwhile, is in the process of splitting its operations into two: Hemfosa, which will remain listed and retain the company’s public sector real estate portfolio, and Nyfosa, which will act as an “agile and transaction-intensive property company”, according to current Hemfosa chief executive Jens Engwall, who will take over the helm at Nyfosa once the split has taken place.

The plan is for Nyfosa to also be listed by the end of the year, which is expected to happen through a stock split, giving current Hemfosa shareholders shares in both companies.

More supply?

Property companies flocked to the equity market between 2014 and 2016 because more investors were seeking to invest in property stocks, given the low interest rates and low returns that were available in the bond market.

“Everyone from the bus driver to smaller and larger institutions all showed a lot of interest in investing in real estate stocks,” says Newsec’s Mr Barclay. “This is still the case, but the interest in direct investments is also increasing.”

He notes that the businesses now looking to enter the equity market are largely single-asset companies, which have been set up as special-purpose vehicles.

In 2018, the only ordinary share issues recorded by Pangea Property Partners were a SKr1.01bn ($118m) rights issue by D Carnegie to finance acquisitions in Stockholm and Västerås, and a listing by Cibus, a portfolio of assets divested by Finnish investor Sirius on Stockholm’s First North exchange for smaller businesses. In the past 18 months, there has only been one initial public offering on the main exchange, for mid-sized Swedish developer SSM in April 2017.

The weaker pipeline for equity capital market deals goes hand in hand with a growing focus on direct investments by Nordic and international institutional money and private equity funds.

Fighting off private equity

The recent takeover offer by US private equity investor Starwood Capital for Victoria Park, the sixth largest stock exchange listed property company in the Nordics, is a case in point – and it underlines a trend of international private equity money targeting listed businesses.

In the case of Victoria Park, the board has recommended to decline the offer. So, especially at a time of lower valuations, are hostile takeovers something other businesses need to be wary of?

Ilija Batljan, chief executive

at SBB Norden, a Stockholm-based business with a focus on public

sector rentals, believes so. “I think all of us need to look at and analyse what kind of consolidation opportunities there may be,” he says. “Otherwise you might just wake up one day and someone is buying you out of the market.”

A typical way to lower the share price discount to net asset value would be to buy back some of the outstanding shares, according to Mr Andersson at Alfred Berg. He points to residential and office real estate business Wallenstam, which has a buyback programme but is using it mainly as a complement to paying a dividend.

Other options include mergers and acquisitions (M&A) among the existing players.

“Valuations and share prices might provoke M&A,” says Citycon’s Mr Kokkeel. “We are keeping our eyes open. If there was an opportunity that was good for shareholders, we would explore it.”

Five to 12?

At times of increased investor demand and after several years of record returns, the question arises: how much longer can such a market environment last? And where is the property clock, or cycle?

“If you had asked me this time last year, I would have said the same thing as today,” says Mikael Söderlundh, head of research and partner at Pangea Property Partners. “We are high in the cycle. Not at the peak yet, but quite close to it in Sweden, with the other Nordic countries perhaps a year behind.”

Pangea expects international investors, institutions and property funds in particular to further increase their exposure to Nordic real estate in 2018.

But as with differences in performance between the different real estate segments, distinctions might be necessary when analysing the cycle for property as a whole.

“There is a difference between real estate companies focusing more on the needs of the public sector, which is more structural, as the need for daycare, elderly care and schools is not going to slow down in the near future,” says Swedbank’s

Ms Breman. “But other sectors like office space are more mature and will heavily depend on global growth developments.”

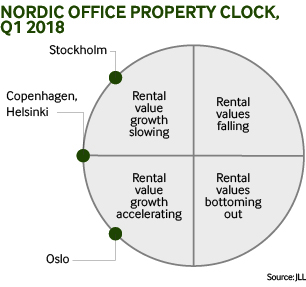

According to the JLL Property Clock for the office sector, as of the first quarter in 2018, Oslo is at about 7.30, still with scope for accelerating rental growth, Helsinki and Copenhagen are at 9, while Stockholm is at about 10.30 (see graph).

“One thing that could cool the market down in Sweden is the new amortisation rules, which were introduced on March 1 this year,” says Mr Söderlundh. However, those have a greater impact on owner-occupied properties. Mr Söderlundh adds that the general elections in September as well as the introduction of interest rate deduction rules later in 2018 could have an impact on the real estate market, too.

Yet the most important factor will remain interest rates, and with them companies’ costs to finance themselves (see articles about bank lending and fixed income on pages 21 and 22, respectively). And while expectations are for an increase in rates at the back end of 2018, the step change is likely going to be slow in coming. Ms Breman expects hikes to be very gradual and only of 10 basis points as a first step, which should mean interest rates, at least in Sweden, remain at zero for the course of 2019.

So the cycle will turn at some point, but likely not in the next couple of years.