The UK's regional divide has been a matter of a growing debate since the Brexit referendum highlighted the deepening partition between different geographies across the country. On one hand, there is London and the south-east, where the wealth is concentrated and the majority of people voted to remain in the EU; on the other hand, there is the rest of the country, where the leave vote prevailed.

This map of Brexit discontent has been deeply explored, and this dichotomy has been taken beyond the conventional urban versus rural approach. Rather, it is a matter of regional divide: communities in wealthy regions, regardless of if they are urban or rural, tend to fare better than their poorer neighbours. In particular, London and the south-east tend to far outperform the UK's other regions country across multiple economic and social indicators.

Advertisement

The distribution of foreign investment across the country is not only consistent with the geography of discontent, but somewhat instrumental to this. Although the capital’s economy is constantly being reinvigorated as high-added-value investment gravitates towards London and the south-east, it has left the rest of the country scrambling for less disruptive investment.

“The country is partitioning. The idea that London can act as the motor of the economy, and its benefits will defuse and pull the country along, is simply not true,” Philip McCann, chair of urban and regional economics at the University of Sheffield and the father of the geography of discontent theory, tells fDi.

Quantitative data

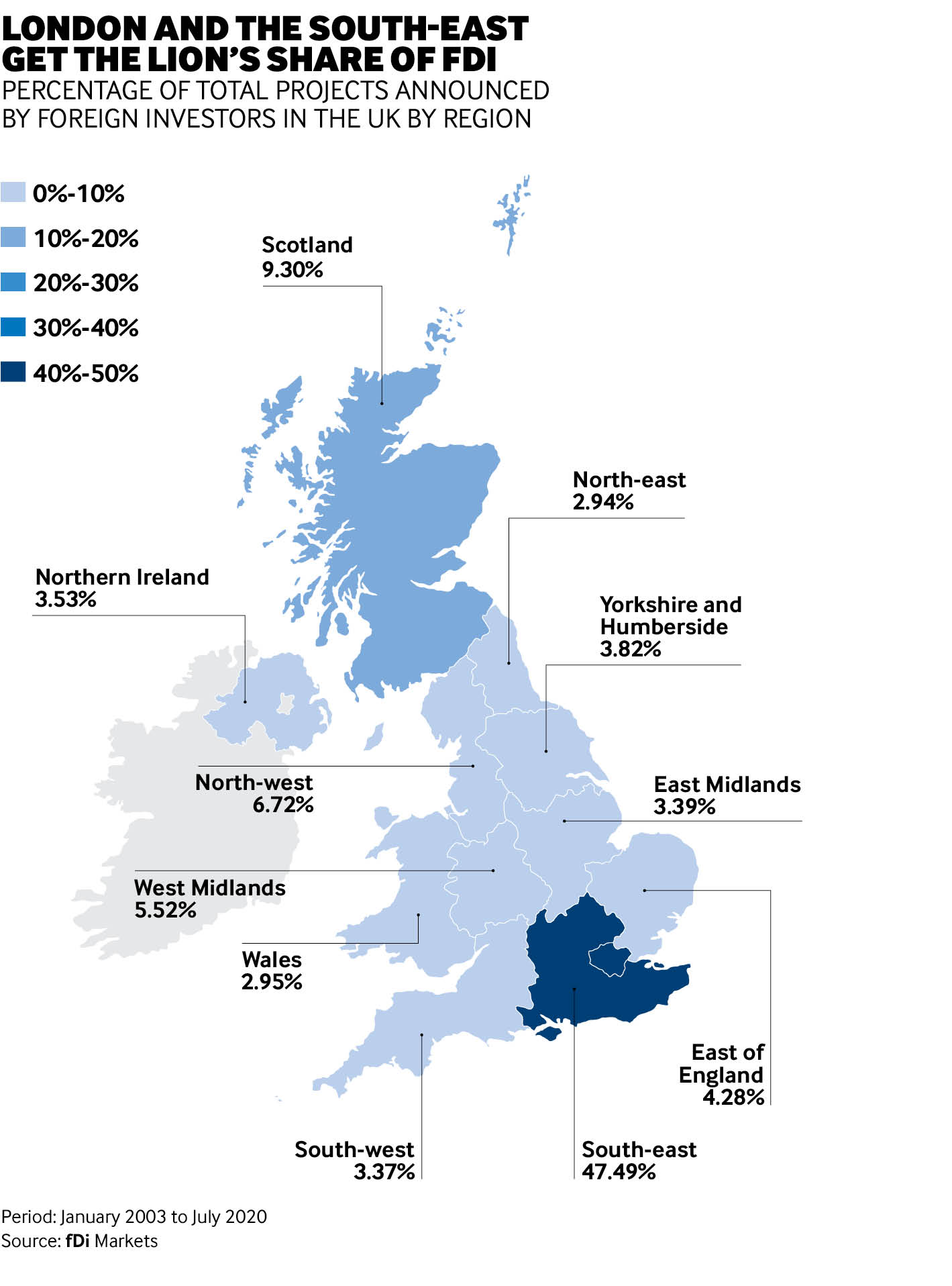

The UK has been Europe’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) for several years. However, London and the south-east have captured the lion’s share of this FDI — overall, they have received 47.5% of the projects announced by foreign investors since 2003, according to figures from investment monitor fDi Markets.

If the south-east of England was itself a country, it would be Europe’s third biggest recipient of FDI, only trailing Germany and France, and the world’s sixth largest, fDi figures show.

“The UK economy has decoupled — it has effectively become two different countries,” Mr McCann says. “London and its broad hinterland is pulling away from the rest of the UK on almost any social and economic indicator, including trade and FDI. This is where the geography of discontent comes from, because people know that the country is partitioning.”

Advertisement

Qualitative data

The country’s FDI largely matches GDP statistics, with London and the south-east making up 43.41% of it in 2018, according to figures from the Office of National Statistics. Mr McCann believes that the country’s FDI distribution is one of the main causes of the region’s disproportionate concentration of wealth.

“It’s not just the magnitude of FDI that is critical here, but also the nature of this investment,” he says. “This is a key feature of the country’s partitioning as foreign investment is one of the most important conduits of knowledge and technological transfer.

“If different parts of the country get different types of investment, then different processes of knowledge transfer linking those places to the global economy take place. London and its hinterland have been getting newer and higher quality investment across the sectors in the past years, whereas investment in the rest of the country has mostly been replacing investment.”

Most of the FDI flowing into the south-east is pure new investment, whereas about one-third of the FDI in the rest of the country is expansion of existing investment or replacing investment altogether, fDi Markets figures show.

Besides, foreign investors located the highest added-value functions in the south-east. Among others, the region captured 61% of the country’s FDI projects into headquarters functions since 2003, fDi Markets figures show. The data also shows that, overall, the south-east grabbed 35% of total FDI into science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) activities since 2003.

Investment into new technologies and start-ups has also gravitated mostly around the capital, facilitating its rise as Europe’s most lively tech hub and the biggest outside the US. The region has captured 54.1% of the country’s total venture capital and private equity investment in 2019, according to figures by the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association.

Scotland a different story

There are notable exceptions though to this pattern, however, in the form of the devolved nations. Scotland in particular punches above its weight when it comes to attracting quality FDI.

“Scotland has enough autonomy and power to get engagement with businesses,” Mr McCann says. “Foreign investors speak directly with the Scottish government, which in turn put them in contact immediately with the supply chain and relevant stakeholders. They are close enough to the action that they can facilitate it straight away.”

Scotland almost matched the south-east with regards to foreign investment into research and development (R&D) functions, attracting 228 R&D FDI projects since 2003 — only slightly lower than the 298 attracted by the south-east. And while Scotland attracted 9.3% of the country’s FDI projects since 2003, that percentage grows to 14% when considering STEM projects only, according to fDi Markets. Northern Ireland and Wales also fare similarly, as their share of the national FDI increases by about two-thirds each when considering STEM FDI only.

In other words, devolved regions seem to be way more successful in focusing and attracting the type of foreign investment that generates the biggest spillover than English regions, suggesting that their greater budgets and autonomy has helped the development of fine-tuned and successful FDI promotion strategies.

Despite clear evidence, the UK's London-centric government has been shy in pushing towards bold wealth redistribution policies. Even Boris Johnson’s ‘levelling up’ and other recent initiatives seem destined to have little impact on the country’s uneven FDI distribution.

“These initiatives are a step in the right direction, but they are on a shoestring — the amount of money involved is very little and the powers of local authorities very little. They have to be done on a much bigger scale,” concludes Mr McCann.

This article first appeared in the October/November print edition of fDi Intelligence.