Have the financial crises of 2007–2015 and Covid-19 ended the earlier era of rapid global economic integration? Or is it just how the economy globalises that will change? The answer is a bit of both.

The history of globalisation of the real economy (trade and foreign direct investment [FDI]) has three features.

Advertisement

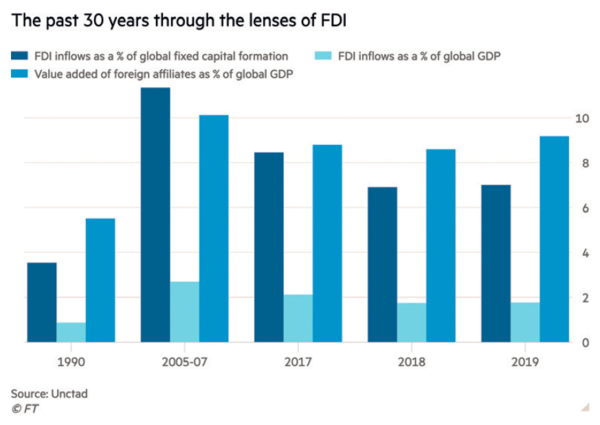

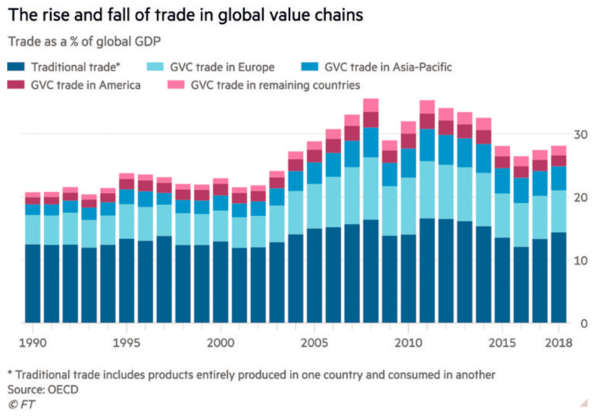

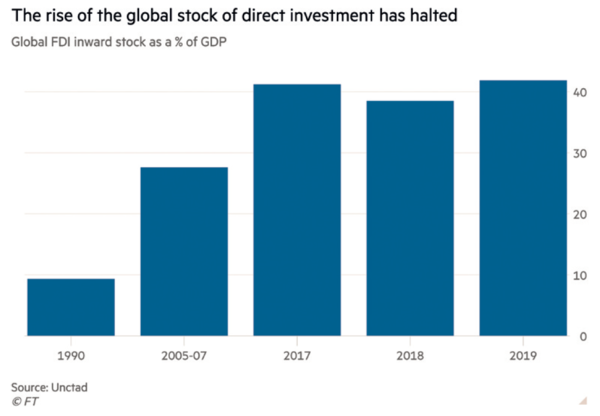

The first is that foreign direct investment and trade are correlated: as trade rises, so does FDI.

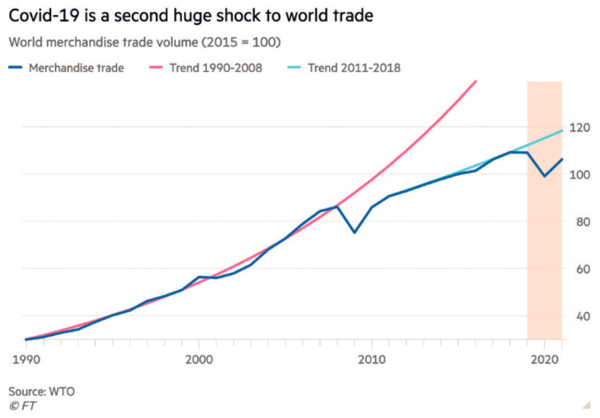

The second is that globalisation has gone through huge cycles: a big upswing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (sometimes called the “first globalisation”); a collapse between 1914 and 1945; a recovery after the second world war, mainly among close allies of the US; and then a global explosion after 1980 (the “second globalisation”), which ended with the global financial crisis in 2007.

The third is that the real side of the world economy was far more integrated at the peak of the second globalisation than it was at the peak of the first.

The rise of globalisation

In brief, the story is one of increasing globalisation over time, punctuated by a collapse in the early 20th century and a slowdown since 2007.

Improving opportunities have driven the long-run tendency towards globalisation. The crucial force has been falls in the costs of transport and communications. In the 19th century, it was railways, steam ships and telegraph cables. In the 20th century, it was container ships, lorries, commercial jets, telephones, computers and the internet.

Advertisement

Opportunities propose; politics dispose. In some periods, policymakers have adopted what the late Chinese politician Deng Xiaoping called “reform and opening up”. During others, policymakers have chosen the opposite. These political shifts are not random: they reflect the impacts of globalisation, macroeconomic instability, great power conflict and nationalist sentiment.

Politically, the globalisation of the late 20th and early 21st centuries was driven by the opening up of China, the fall of the Soviet empire, the liberalisation of India, the Uruguay Round of trade liberalisation, and the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and China’s accession to it.

Economically, the opportunity was to incorporate billions of cheap workers into the global economy via trade and FDI. Radically improved communications technology and speedy and cheap transportation allowed successful management of supply chains across frontier. This drove new patterns of trade and direct investment managed within multinational corporations.

The peak of globalisation

This era of globalisation brought rapid global economic growth, reductions in global inequality for the first time since the 19th century, and an extraordinary decline in the proportion of the world population in extreme poverty. Yet, by spreading know-how and production across the globe, globalisation also forced the industrial workers of high-income economies into competition for jobs with workers across the globe.

Then came the financial crisis and the “great recession”. This was a turning point. Globalisation did not collapse, as it had after the great depression of the 1930s. But it peaked.

What explains this dwindling of the earlier dynamic? It was partly the declining opportunity to unbundle supply chains further. This was due to several changes — the sharp reduction in the wage gap between China and high-income countries, the tendency for supply chains to move fully within China, the reduced appeal of free-market ideologies, the abandonment of global trade liberalisation, the weakening of global co-operation and the emergence of a substantial amount of outright protectionism.

The start of deglobalisation

Thus, both natural and politically-driven obstacles slowed the pace of globalisation after the post-crisis recovery. Brexit is one example of politically-driven deglobalisation.

Far more important, however, was the accession of Donald Trump to power in the US and the trade wars he launched, notably against China. As had happened in the early 20th century, great power rivalries became increasingly significant in shaping policies towards trade and FDI. Particularly significant, in this context, has become the concern over technological sovereignty, shown, above all, by the war against Huawei.

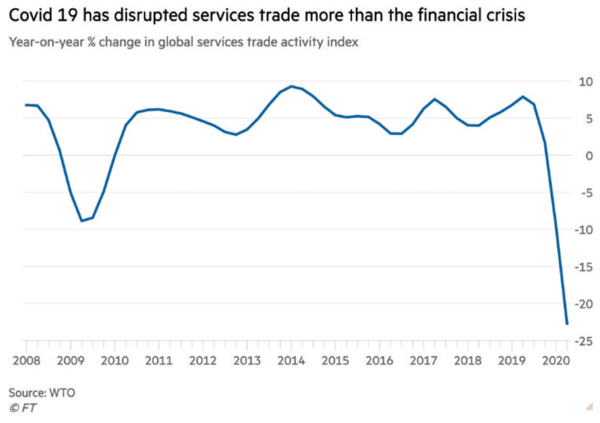

Then came the huge shock of Covid-19. The WTO has estimated that the volume of global merchandise trade will shrink by 9% this year, the second biggest decline since the second world war. The question then is what will follow.

Covid-19 has reminded businesses and governments of the risks associated with long and complex supply chains. But, as lockdowns have shown, domestic production is not necessarily secure either. The tendency, however, is likely to be an increasing awareness of the risks of disruption and so to build greater robustness and resilience into any plans for global production.

Above all, the response to Covid-19 has been predominantly national, and has also led to demands for a better domestic availability of good job opportunities. The medium-term outcome then is likely to be greater economic nationalism and protectionism, even after the defeat of Mr Trump. The rivalry between China and the high-income countries is sure to reinforce this tendency.

This tendency away from global integration is also reinforced by movement towards regional integration — most recently agreement on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which combined China with Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and ten south-east Asian countries. But such regionalisation is also likely to be both contested and incomplete, especially in the vast Asian region.

Ultimately, however, opportunities are likely to trump politics, as they have in the past. While the opportunities to further integrate production systems for goods have diminished, opportunities to integrate digitally have clearly increased. When the ability to share information and work together across the world has reached such unprecedented levels, will the consequent opportunities to develop closer economic links be thwarted indefinitely? The answer is likely to be no.

Big questions have now arisen bout the future of globalisation and especially about how politics will shape it. But, in the long run, economic opportunity shapes reality. It did so in the past and will do so again. But, realistically, the interludes of resistance to taking those economic opportunities can also be rather long.

This article first appeared in the December/January print edition of fDi Intelligence.