Refugees demonstrate remarkable drive. They have experienced persecution and harrowing political conditions and yet they are more entrepreneurial than anyone else. And they often excel. Examples include Madeleine Albright in government, Sergey Brin in technology, Albert Einstein in science or Wyclef Jean in music.

In this piece we show that refugees also contribute to the economic development of their origin countries, sometimes many years after they have left, by fostering foreign direct investment.

Advertisement

Evidence from the Vietnamese Boat people

David Thai fled Saigon by boat in 1975, when the communist North invaded the South. At age six he found himself in Seattle. There he witnessed the success of Starbucks. Years later he established his own chain of coffee shops in Vietnam, Highlands Coffee. It now operates 230 coffee shops.

Than Phuc also fled Vietnam in 1975. As the former CEO of Intel Vietnam, he was responsible for the first bigtech foreign investment in the country. In 2006 Intel invested $1bn in a chip testing facility that created 4000 jobs.

Henry Nguyen was not even two years old when he landed in the US. He grew up flipping burgers in suburban Virginia. In 2014, he brought McDonald’s to Vietnam.

David Duong’s family had to be rescued at sea after fleeing on a small boat. They started a recycling business after settling in California. In 2015 David expanded into Vietnam with a $450m investment that created more than 400 jobs.

Our research suggests that these are not isolated examples. The Fall of Saigon triggered an exodus of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese. The first wave of some 125,000 Vietnamese refugees were admitted to the US in 1975.

Advertisement

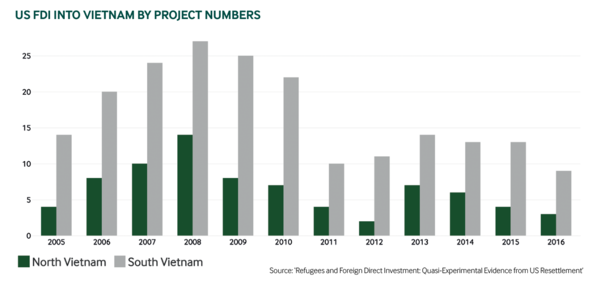

Our research shows that FDI to Vietnam in the past 15 years came mostly from those US cities that hosted greater numbers of refugees. A 10% increase in 1975 Vietnamese refugees is associated with a 0.41% increase in FDI to the south of Vietnam between 2005 and 2015. These numbers are based on data from fDi Markets and from the Office of Refugee Resettlement, a division of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

These effects are not driven by the fact that Vietnamese refugees all chose to live in Los Angeles or New York, to be best placed to do international business. When refugees first settled, there was no prospect of doing business with Vietnam due to US sanctions. Moreover, refugees did not even decide where to settle down.

Congress mandated that the refugees be scattered across the country, to avoid a similar agglomeration as had occurred with Cubans in Miami. Vietnamese refugees ended up dispersed across 400 different locations in the US, and in places like Houston and Minneapolis. These initial resettlement locations persisted, as the first comers attracted waves of refugees in the following 20 years. It is this initial quasi-random resettlement process that allows us to interpret our results as a causal effect of refugees on FDI.

Since 1994, when US sanctions, were lifted, the government of Vietnam has implemented several policies aimed at engaging overseas Vietnamese as part of its overarching growth strategy. These include the 2005 Investment and Enterprise Laws and the 2008 Nationality Law. The reforms created a more favourable environment for overseas Vietnamese investors, and included tax incentives and rent exemptions. While these laws did increase US FDI to Vietnam, FDI increased far more from those cities that hosted larger numbers of Vietnamese refugees.

The case of Vietnam suggests that developing country policies can leverage overseas diasporas for development via FDI. Refugees often maintain close ties to family and friends in their countries of origin, and have extensive knowledge of their home markets, languages and customs. Refugee networks provide information on local business opportunities, help maintain trusting relationships and make FDI happen.

Evidence from refugees from all around the world

These effects are not unique to refugees from Vietnam. Our research highlights that this FDI effect is prevalent on average across all refugee origins. The early 1990s witnessed large refugee inflows to the US, notably from Vietnam but also Russia, Ukraine, Iraq, Myanmar and Bosnia and Herzegovina. US agencies were again in charge of assigning places of residence for those refugees without pre-existing family ties in the US. These refugees did not get to choose the best place to do business with back home. Instead, refugees from each of the origin countries were spread across more than 50 cities on average. We use this quasi-experimental allocation to once more provide causal estimates of the effect of refugees on FDI.

Our analysis combines confidential data on refugees resettled in the US between 1990 and 2000 from the Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System, with data on FDI from fDi Markets.

We find that across US cities, a 10% increase in refugee arrivals between 1990 and 2000 increases outward FDI flows to their countries of origin between 2005 and 2015 by 0.54%, FDI projects by 0.24% and FDI jobs by 0.72%. These effects are surprising given the persecution refugees once fled and given the far-from-ideal political conditions that may persist in their origin countries. We find refugees explain a considerable share of US FDI to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Haiti, Liberia, Moldova and Somalia, for example.

To put it simply, when US companies invest in the countries of origin of refugees, it is most often from those cities that host larger numbers of refugees.

How can we be sure it is not pre-existing communities of co-nationals that attract refugees and foster FDI, rather than the refugees themselves? To make sure this is not the case, we examine the effect of refugees on FDI in cities where there were no economic migrants of the same nationality whatsoever in 1990, before the refugees arrived. In those cases, we can be assured that the FDI effect we measure is due to the refugees.

Development via FDI

FDI is an essential ingredient for economic development and long-lasting stable relationships between origin and destination countries. FDI can create good jobs, facilitate technology diffusion and create links with local businesses. FDI is also less likely to experience capital reversals in times of adverse economic shocks. Yet developing countries often struggle to attract investment. Despite the difficult circumstances under which refugees fled, our research shows that these same individuals can foster FDI to their countries of origin. Our research thus highlights that decisions taken primarily for humanitarian reasons in developed host nations may yield economic benefits for some of the world’s poorest nations.

Dr Pierre-Louis Vezina is an associate professor in economics at King’s College London. This article is based on the following academic paper: Mayda, A, C Parsons, H Pham and P-L Vezina (2019), ‘Refugees and Foreign Direct Investment: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from US Resettlements’, CEPR Discussion Paper 14242.

This article first appeared in the February/March print edition of fDi Intelligence.