The pressure was on for companies to take a stand as soon as Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine on February 24. Several energy companies, among the most exposed to the Russian market, came out publicly right away.

“I have been deeply shocked and saddened by the situation unfolding in Ukraine,” said Bernard Looney, BP’s CEO, on February 27. “It has caused us to fundamentally rethink BP’s position with Rosneft.”

Advertisement

Mr Looney’s statement came as he announced the sale of the 19.75% stake of Rosneft that BP owned, while noting it could possibly lead to losses of $25bn.

A few hours later, Anders Opedal, president and CEO of Norwegian energy company Equinor, followed suit. “We are all deeply troubled by the invasion of Ukraine,” he said on February 28 as he announced the company’s divestment of its Russian assets. “In the current situation, we regard our position as untenable.”

These statements marked the start of a widespread retreat by Western brands and investors over the following weeks. Hundreds of companies announced divestments of Russian assets, or suspended their local operations to answer or pre-empt calls to do so from their shareholders, customers, employees and governments.

As the war progressed, public debate shifted from those that were taking action to those that were not — as has happened with companies operating in other conflict zones such as Xinjiang, China, or the occupied Palestinian territories, which further highlights the growing pressure for businesses to either ‘do the right thing’ or be publicly singled out for not doing so.

If corporations had already become assertive with regards to several socio-political issues beyond their typical corporate social responsibility programmes or lobbying activities — particularly during the years of the Donald Trump presidency in the US (2017–2021) — the Ukraine war is a watershed moment for corporate activism and stakeholder capitalism as a whole.

Gone are the days when CEOs abided by the old mantra: “Do not mix business with politics.” Gone are the days when shareholders were supposed to be the only stakeholders of concern. Rather than simply complying with regulations and sanctions, global firms are embracing a bigger role to reflect and address the expectations of the widening base of stakeholders they respond to. By doing so, they contribute directly to shaping up the economic, as well as socio-political agenda of their own countries, as well as the countries they operate in.

Advertisement

Companies picking sides has already affected global trade and investment patterns, and will further contribute to fragmenting global markets along the lines of the new, emerging multipolar order.

More influential than ever

The growing role that companies play in issues that go well beyond their business mandate, and may even negatively affect their bottom lines, reflects a much broader structural change in the balance of power in liberal democracies.

“Politically, private corporations are the most influential interest group out there at the moment,” says Michael Nalick, an assistant professor of management at the University of Denver, Colorado. “Because of the power they have amassed, it’s almost a natural progression for them to branch out into other areas. Governments have weakened overall, while the private sector is now taking on roles that the government used to play when it comes to providing or financing basic services, like education.”

If ever more powerful multinational corporations are the result of globalisation and its worldwide opportunities, their socio-political activism is somewhat rooted in the disenchantment with that type of profits-driven, shareholder capitalism that climaxed at the beginning of the century, only to implode with the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007/08.

“After the GFC, companies had to take a lead to make their business legit again,” says Laura Marie Edinger-Schons, a professor of sustainable business at the University of Mannheim, Germany. “They took a critical attitude towards a shareholder approach and shifted to a stakeholder approach. Now if they talk about values, they must look at the values of their whole stakeholder base. Once they start talking about socio-political issues of sustainability, they create pressures to live up to these expectations.”

Turning tide

With Western public opinion coming together in unanimous condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it was almost a no-brainer for energy companies dealing directly or indirectly with the Kremlin to withdraw from Russia, even at high costs and as the Kremlin paved the legal route for national appropriation of the fleeing companies’ assets. The same applies to consumer goods companies, whose reputation among their customer base was on the line. It was less of a straightforward decision for many other services and business-to-business companies active in the Russian market, many of which still followed suit.

What appears a foregone conclusion today may have played out differently only a few years ago. During his presidency, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly made use of military force. The Russian army razed the Chechen capital Grozny to the ground in 1999/2000; invaded Georgia in 2008; invaded Ukraine’s Donbass and Crimea regions in 2014; and got dispatched to Syria in the following year. This all caused outrage in the West and sometimes led to sanctions, but did not throw into question the involvement of Western companies in Russia.

Instead, Mr Putin continued to meet with foreign businesses throughout — he met with the CEOs of some of the biggest Italian companies as late as January, as Russian tanks were amassing along the Ukrainian border.

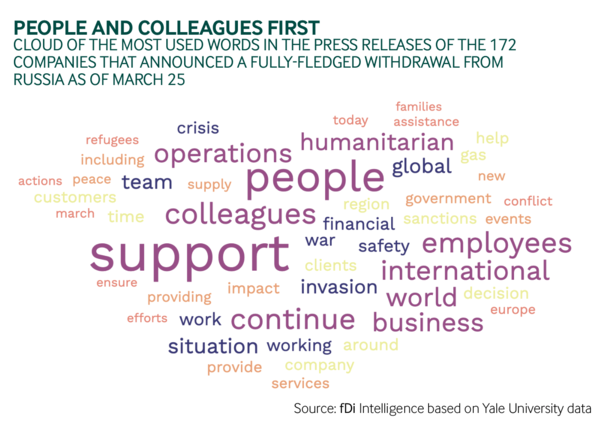

However, the tide turned on him as soon as the invasion began. As of early April, six weeks into the Ukraine war, more than 600 companies have announced their withdrawal from Russia, according to an ever-growing list compiled by Yale University.

“I don’t think we’d have seen the same reaction 10 or 20 years ago,” Glenn Fogel, CEO of online travel platform Booking Holdings, tells fDi. “The role of business has changed over time. Today, companies have a moral obligation to understand all the elements of business and its impact on the world … It means taking into account all the stakeholders, and having a point of view. I believe we can endorse a stakeholder approach without compromising on the bottom line.”

Booking.com decided to suspend the services they provided to customers in Russia and Belarus — which sided with Russia at the beginning of the war — as “sanctions made it very complex” to operate in those regions, Mr Fogel says.

Under pressure

Mr Nalick highlighted in a 2016 research paper that companies pick sides on specific socio-political issues to act on “stakeholder pressure recognition”, where stakeholders pressure the firm into unwanted, unplanned actions.

Although the current situation is different to the socio-political issues examined by the paper (which looks at US gun legislation, refugee immigration and same-sex marriage), it is a case in point. The pressure from customers, employees, governments in their home countries and shareholders too for companies to pull out of Russia suddenly snowballed as soon as the Kremlin gave the order to invade its neighbour.

“Most companies that decided to leave did so not because they were legally forced to — most of them had a choice to stay and continue, at least on paper,” Guido Palazzo, professor of business ethics at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, tells fDi. “But this was a very special situation where almost the entire public opinion in Europe is against companies that want to stay. They can’t win a fight against public opinion that is so inherently against them [staying in Russia].”

The customer-facing companies that were slow to act quickly paid a price for it, with the likes of Swiss food and drink powerhouse Nestlé being put under the spotlight by the public as a result. For other services, such as business-to-business companies, the pressure mounted not from outside, but from within.

“I’m an old-fashioned type of capitalist, I avoid making ethical and political decisions,” Mark Weil, CEO of TMF, a consultancy firm that provides compliance and administrative services around the world, including in Russia and Ukraine. “I didn’t have any client coming to me and asking to withdraw from Russia, I acted for our colleagues,” he says in reference to the company’s decision to stop services to Russian clients.

“There are plenty of conflicts in the world and, although we work in 85 jurisdictions, [most of them] are not really affecting our people. This time it was different, though, because our employees in Ukraine are direct victims of the conflict.”

Where do we go from here?

This exodus sets a precedent for any company that pulled out of the country for reassessing assets and operations in other geographies.

“There is a generational shift going on,” Mr Weil says. “From my perspective, as long as we can guarantee the safety of our people, the rule of law and the hygiene factor [particularly around communicable diseases], then we will do business. But today there is an increasing imperative for companies to avoid certain clients, sectors or governments that we don’t like ... Once we step over that line, we are not fully in control any more. If there were colleagues exposed to a conflict elsewhere, then we would feel obliged to take similar steps. Once we make that choice, it becomes harder not to do the same next time.”

Covid-19 had already caused a reassessment of operating in certain foreign countries

The Ukraine war has happened at a time when multinational corporations were repositioning following the Covid-19 crisis, and the supply chain disruptions it brought along.

“I do see global corporations reassessing their global footprint,” Mr Nalick says. “Covid-19 had already caused a reassessment of operating in certain foreign countries, and the Ukraine war adds to that by raising the risk of operating in autocratic countries or illiberal democracies. There will be a lot of social pressure for companies to pull out [of certain countries] also when exposure is indirect and comes from the supply chain. For example, before the war, there had been no business assessment of the risks stemming from the China/Taiwan situation. That’s not the case any longer.”

China is an easy guess for a country that is currently being reassessed in Western boardrooms. According to fDi Markets figures, foreign direct investors have already limited their engagement with China since the outbreak of the Covid pandemic as the country moves towards a more inward-looking, consumer-driven growth model, and president Xi Jinping cements its power along the way. This sentiment has now extended to financial investors, with the Institute of International Finance (IIF) reporting unprecedented outflows of capital leaving the mainland’s financial markets.

“At this stage, it is too early to say if the war is driving outflows or if other factors are to blame,” the IIF said in a research note on March 24. “But we think these outflows are notable enough to at least raise the possibility that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may be pushing global markets to look at China in a new light.”

The evolving position of direct, as well as portfolio, investors may come as no surprise as the mounting wave of environmental, societal and governance (ESG) finance, with shareholders holding boardrooms accountable to increasingly higher standards of ESG practises, is already factoring in some of the lessons coming from the Ukraine war.

“Responsible investors will also need to closely scrutinise and consider exiting investments in, or ending financing of state-affiliated entities and any other entities or individuals that are arming, financing or otherwise contributing to violations of humanitarian and human rights laws,” wrote ShareAction, a UK-based responsible investment charity, on March 7.

Multipolar world

ESG and socio-political issues are now at the top of the agenda of the annual general meeting season currently underway.

With the US-sponsored, liberal world order that dominated the world economy since the fall of the Soviet Union coming to an end, “we’re in a world where companies and countries must take sides with the value system they feel closest to”, says Mike O’Sullivan, an author and economist who believes that globalisation is coming to end and will be replaced by a multipolar world order shaped by three main centres of power: the US, Europe and China-centric Asia (see page 24).

Companies’ boardrooms are well aware of this situation.

“In the same way as after the first and second world war, after the fall of the Soviet Union, we have to think about what the world order will look like,” said Carl-Henric Svanberg, the chairman of car producer Volvo, in an interview with the company’s CEO Martin Lundstedt, published on the company’s website ahead of the company’s annual general meeting on April 6. “How it will affect free trade, how we are going to secure supplies ... but [also] how we will work together in the world. There will probably be some changes.”

Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows have already been reflecting a growing alignment of values between investors and destination countries. The percentage of FDI projects located in OECD countries — generally perceived as the custodians of liberal markets and democracies — that originates in the same OECD countries has been constantly growing since 2003. It stood at more than 68.4% of total FDI projects worldwide in 2021, from 41.4% in 2003, according to figures from investment monitor fDi Markets.

In terms of value of capital investment, a record of 65.8% of the global FDI capital expenditure announced in 2021 was a pure OECD play in terms of both origin and destinations. On the other hand, investors from OECD countries have been quietly reducing their exposure to Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. FDI projects into Brics countries by investors coming from OECD members accounted for a record low of 6.8% of the global FDI projects announced in 2021, down from a peak of about 26.2% in 2004, fDi Markets figures show.

In other words, investors from OECD countries, typically the biggest source of cross-border investment, have been showing a growing propensity to do business with like-minded partners in like-minded countries abiding by the same liberal standards outlined by the OECD.

People definitely admire those countries that do good, that protect the environment, that avoid wars

Eventually, the way global companies will deal with cross-border investment in the foreseeable future may come down to the perceptions of those individuals who make up their stakeholder base as shareholders, customers, employees or executives and regulators.

“People definitely admire those countries that do good, that protect the environment, that avoid wars,” says Simon Anholt, an independent policy advisor and founder of the Good Country index, which measures the way each country contributes to the planet, and the Nation Brands index, which monitors global perception of single countries. “There is evidence that countries with strong ESG credentials, those that welcome migrants and have a sustainable energy agenda, are the ones that increasingly have the edge when it comes to FDI and talent attraction. These two strands are weaving together in a very encouraging way.”

For some, perception is reality, and in a capitalism where the stakeholder approach is mainstream, the future of cross-border investment hinges on the perceptions of all the individuals that form and shape up the stakeholder base of corporate activists. Pariah states will pay the price for it.

Jiyeong Go contributed research for this article.

This article first appeared in the April/May 2022 print edition of fDi Intelligence.