The push by European countries to align net-zero ambitions with the need to address rising energy security concerns following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created unprecedented momentum for capital-intensive offshore wind energy development across Europe.

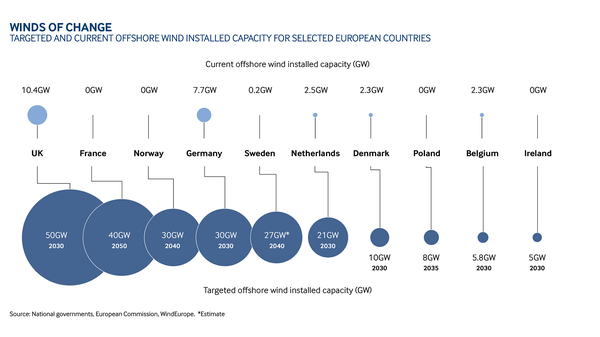

The EU has set a target of 150 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind installed capacity by 2030, which is set to double to 300GW by 2050. Outside the EU, the UK is looking at 50GW by 2030 and Norway is targeting 30GW by 2040. With 1GW of installed capacity being roughly enough to provide power to one million people, European policymakers hope these targets will be enough to cover the needs of the majority of people living on the continent.

Advertisement

However, the gulf between hope and reality is wide. Europe’s current offshore wind capacity is almost exclusively concentrated in a handful of North Sea countries, which combine for 25.2GW of offshore wind installed capacity — as much as 10.4GW is installed in the UK alone and another 7.7GW in Germany, according to official figures compiled by fDi Intelligence. The rest is spread mostly between Denmark, the Netherlands and Belgium.

There is little installed capacity elsewhere in Europe. The typical cost of offshore wind projects raises other challenges, particularly in the current inflationary environment, which heightens the risk associated with future cash flows.

While developers believe scale and capital requirements can be overcome, the bureaucracy around offshore wind projects makes meeting these targets seem unlikely. Supply chains are becoming increasingly tight, with major producers already sending distress signals to the market.

Red tape and supply chains

“The permit and consenting time take an average of seven to 10 years for each project,” Michael Hannibal, partner at Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), an asset manager that participates as a direct investor in greenfield renewable energy projects, tells fDi. “That has to come down. These projects have been done again and again, and there is a lot of knowledge that can be used to speed up the process.”

EU authorities have acknowledged the issue and shown renewed commitment to address it. Long permitting times are the “elephant in the room whenever we talk about rapid deployment of renewables”, said Kadri Simson, the EU’s commissioner for energy, in a statement on May 18. She also took the opportunity to announce an action plan to accelerate permitting by introducing “go-to” areas where permitting procedures “shouldn’t take more than a year.”

Advertisement

Across the Channel, the UK government pledged to cut the approvals process for offshore wind down to one year and set up a fast-track approvals route for priority projects, in its new energy security strategy, unveiled in April.

“Another challenge is that we need to see a strong supply chain being able to ramp up manufacturing to deliver more turbines and equipment. In order to do so, they need to have sustainable businesses, and so their suppliers,” Mr Hannibal says.

The three biggest non-Chinese wind turbine manufacturers — Danish Vestas, German Siemens Gamesa and US General Electric (GE) — all reported net losses in the first quarter of 2022. “Profitability was heavily impacted by highly disrupted supply chains and one-offs [related to the war in Ukraine and the resulting sanctions on Russia],” Vestas’s president and CEO, Henrik Andersen, wrote in the financial report of the first quarter of 2022. Vestas and Siemens have also revised downwards their full-year guidance; while GE held the financials range provided in January, it is trending towards the lower end of that range.

Christoph Zipf, a spokesperson for Wind Europe, an association promoting the use of wind power in Europe, tells fDi that disrupted supply chain creates “additional pressure” on the European wind industry. Ultimately, he says, they risk raising the electricity price generated by offshore wind as developers try to transfer equipment inflation onto off-takers.

Stronger case for renewables

On the other hand, the demand, if not the need, for new renewable energy capacity across Europe has soared to new heights.

“The growing energy crisis, however, also led to stronger political support for renewables to enhance energy independence and keep energy prices low,” Mr Andersen noted.

The day after the EU announced its REPowerEU plan on May 18, Belgium, Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands issued a joint statement where they committed to jointly developing 65GW of offshore wind power installed capacity in the North Sea by 2030, and 150GW by 2050.

“The recent geopolitical events will accelerate our efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption and promote the deployment of renewable energy for more energy resilience in Europe,” the joint statement reads.

Also in May, Norway announced its intention to develop 30GW of offshore wind installed capacity by 2040. Earlier in the year, the British government hiked its offshore wind target by 25% to 50GW by 2030, as part of its new energy security strategy and Sweden announced plans to develop offshore wind energy able to produce 120 terrawatt hours, for an estimated installed capacity of 27GW.

Available capital

Achieving these targets will require billions in capital expenditure (capex) from both domestic and foreign developers.

In the North Sea, offshore wind projects require between €1.1bn and €1.6bn of capex in transmission equipment and costs per GW, along with an additional €0.8bn to €1.3bn for generation, according to a research paper published by the European Commission in November 2020.

Despite its extreme capital intensity, the market’s appetite for these projects seems to have survived the turmoil caused by soaring inflation and the Ukraine war.

“There is still a good appetite for institutional investors to come in and support renewable and energy transition projects for climate and geopolitical reasons. Climate change and the unfortunate events in Ukraine have driven volumes [of activity] up in the market,” Mr Hannibal says.

Inflows in European sustainable funds, as defined by Article 8 and Article 9 of the EU’s sustainable finance directive regulation, continued to grow in the first quarter of 2022, according to figures from the financial services company Morningstar. The energy research firm Rystad estimates that annual capex into European offshore wind will stand at $53bn in 2030, thus growing by a factor of 3.4 from $15.7bn in 2021.

Provided large amounts of capital remain available, innovation will also help European countries reach their offshore wind energy targets. Denmark, the country that first brought an offshore wind park online in 1991, has launched a programme to develop artificial energy islands to provide large-scale offshore wind developments feeding into the grids of different North Sea regions.

Outside the North Sea, floating technologies are creating new opportunities for countries looking at offshore wind developments on the French Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

However, European countries are facing a colossal endeavour. The North Sea countries alone will have to install around 11GW per year of new offshore wind capacity in the next few years to meet their 2030 targets. Last year, only 3.4GW was installed across Europe. And some of the most ambitious offshore wind targets come from the likes of France, Norway and Sweden, with little or no utility-scale offshore wind capacity currently installed, which inevitably raises questions about their capacity to walk the walk.

If anything, though, the Ukraine war was another wake-up call for the continent to speed up its energy transition. With clear political commitment no longer in doubt, there is no turning back. This endeavour has become exclusively an execution challenge.

This article first appeared in the June/July 2022 edition of fDi Intelligence.