The writing has been on the wall for years, but companies took notice only in the wake of the pandemic.

“Technology companies were forced to figure out how to work remotely,” Ben Horowitz, the co-founder of Andressen Horowitz — one of the world’s most established venture capital (VC) funds — wrote on July 21. “It turns out that running a technology company remotely works pretty darned well.”

Advertisement

The time was ripe for change.

“Our headquarters will be in the cloud, but we will continue to create physical offices globally where needed to support our teams and partners,” Mr Horowitz announced.

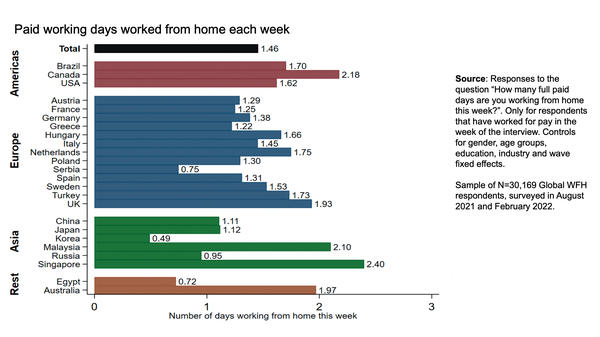

It’s not just tech companies that have embraced the remote work revolution. A wide array of services companies have introduced fully remote or hybrid work arrangements as the pandemic disrupted the traditional office-based paradigm. Even in manufacturing, the use of automation, 5G broadband and Internet of Things technology mean that most, if not all, tasks can be controlled remotely. South Korea’s Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute has successfully proved it can monitor and control a smart factory in Gyeongsan in real-time from Oulu, Finland, some 10,000km away.

“The main victim of the pandemic has been Frederick Taylor,” Gianpaolo Barozzi, senior director for people and community at Cisco tells fDi, referring to the late American mechanical engineer and his method of workflow management, which have shaped industrial relations and models of work throughout the 21st century.

With work becoming more mobile, a more talent-oriented approach to economic development and investment promotion has gained momentum, with cities around the world willing to seize a once-in-a-lifetime chance to compete for talent with traditional business hubs and rectify a decade-old brain drain.

“Places that typically struggle to compete and attract new industries or anchor employers can leverage the remote worker model to gradually build up their pool of skilled workers outside of the traditionally pricey method of incentivising employers to relocate," reads a 2021 report by the Washington DC-based research organisation Economic Innovation Group (EIG). “By bringing in many independent remote workers, communities can work around the ‘chicken and egg’ problem of having to attract skilled workers without a major employer, since the local employer is no longer a prerequisite.”

Advertisement

The jury is still out on whether this talent-first approach can pay dividends in the long run.

Turning back the clock in Venice

“In the past, the success of a city hinged on its capacity to attract companies; today it hinges on its capacity to attract talent too,” says Massimo Warglien, a professor of management at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy, and founder of Venywhere, a programme designed to lure remote workers into choosing Venice as their base.

“We came up with this idea during the pandemic,” he adds. “On the one hand, it addresses the fragility of a tourism city with a major demographic problem; on the other hand, it seizes the opportunity stemming from a growing pool of mobile workers. For cities like Venice, it’s a unique development opportunity.”

Known for its breathtaking canals and rich history, Venice’s days as a business centre have long passed. Once the biggest trading hub in the Mediterranean Sea and a force that any European ruler had to reckon with, contemporary Venice is a postcard city for international tourists. Venice’s contemporary tourism vocation has been a boon for local entrepreneurs in hospitality, but has also driven thousands of inhabitants out of the city centre. After peaking at 175,000 in 1951, the population has plummeted over the years, falling below 50,000 in 2022, according to local official figures.

Venywhere now hopes to sow the seeds in reversing this trend, breathing new life into the city beyond tourism and art.

The programme has three main pillars: soft landing services, an offer of workspaces across the city, and community engagement initiatives. These are designed to encourage remote workers to go beyond a ‘workation’ and stay for up to 24 months, although Mr Warglien hopes “some of them can stay here forever”.

“The idea is to stabilise a community of workers beyond art and tourism that can make it an appealing place for other workers to move in,” he adds.

Venywhere has been piloted by tech company Cisco, which set up a team of 16 employees that worked from Venice for three months in the first half of 2022. The programme is now launching in its fully-fledged version and has already seen 2600 people signing up.

“We are moving towards an idea of distributed work,” Mr Barozzi says. “Companies need to take leadership in embracing this cultural shift as technology enables it.”

Different public and private institutions around the world have set up similar initiatives to attract mobile talent.

Helsinki Partners, the investment promotion agency (IPA) of the capital city of Finland, launched “90-day Finn” in 2020, a programme offering a 90-day relocation package for entrepreneurs, investors, corporate executives, event organisers and tech talents — as well as their families — to move to the city for three months while developing their business and ideas.

From the 5000 applications the programme received in 2021, it selected 13 professionals. Helsinki Partners reports that at the end of the 2021 programme’s three months, two new companies were founded and registered in Helsinki, and more than half the programme’s participants stayed in the country for more than 90 days. The programme’s 2022 edition is now underway.

Across geographies, from Zadar in Croatia, to Dubai in the UAE and Bali in Indonesia, cities are increasingly targeting remote workers and digital nomads to relocate, spend time and money locally and connect with local communities. By doing so, they all hope to set in motion a virtuous talent development cycle able to lift the local business and investment appeal.

Take me to Tulsa

Nowhere has become a global poster child for the development of remote worker attraction programmes quite like the US city of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The brainchild of the local George Kaiser Family Foundation, Tulsa Remote launched in 2018 as a programme offering $10,000 grants and an array of community-building opportunities for remote workers willing to relocate to the city for a year.

Justin Harlan, the managing director of Tulsa Remote, tells fDi that the Covid-19 pandemic has dramatically increased interest: “In 2019, [the first year of the programme], there were 60 members. In 2020, we had 350. And then in 2021, we had 950. So far, we’ve brought about 1800 folks to town.”

A quarter of them are “boomerangs”, he adds — professionals who returned to the city after starting their careers elsewhere.

The programme requires its members to have a full-time remote job, but it connects aspiring entrepreneurs with resources in Tulsa, whether that’s the downtown start-up incubator or local VC firms.

“We’ve heard time and time again that the $10,000 grant is what maybe brought people to the city, but it’s the community that helps them to stay,” says Mr Harlan.

Growth from within

Tulsa has become a blueprint for other urban communities to replicate, and a symbol of the paradigm shift happening in economic development.

“At $10,000 per worker, the cost of these programmes is much lower than typical corporate attractions, which in the case of manufacturing companies can be as high as $200,000 per job,” Kenan Fikri, director of research at EIG and Daniel Newman, research and policy analyst at EIG, tell fDi.

“The risks involved are much lower and target the natural feedstock of economic development: human capital. A traditional approach to economic development resembles elephant poaching in its hunt for big corporate relocations. This is the opposite model.

“Attracting remote workers is done more in the spirit of ‘economic gardening’ [or a growth from within model], and making sure that the key ingredients for growth and prosperity are available in local economies, specifically human capital.”

According to makemymove.com, there are now 151 cities in the US offering incentive packages to attract remote workers. Tulsa Remote, established in 2018, is one of the oldest and biggest, with 20,000 applications last year.

“I suspect Amazon’s HQ2 saga was an eye-opener [for cities to start focusing on attracting talent],” says Mr Fikri. In 2017, Amazon put out a request for proposal for any city willing to bid for its planned second US headquarters. “Economic development organisations (EDOs) across the country competed for it. Once the project went to New York and Arlington, just next to Washington DC — mostly because of the existing local talent pool — many felt they had never stood a chance, which added more insult to the injury than they could take.”

Companies go remote

Talent-centred economic development initiatives have been further validated by the strategies of many private firms, focusing on talent availability and new forms of work in the wake of the pandemic.

Just a few months into the pandemic, in May 2020, Meta’s (then Facebook’s) CEO Mark Zuckerberg estimated that over the course of the next decade, half of the company could be working fully remotely.

A flurry of similar announcements followed. Earlier this year, tech companies of the likes of, among others, Airbnb, Spotify and Twitter, announced work from anywhere arrangements while cutting down on office space in San Francisco and elsewhere. Mr Horowitz elaborated on this shift in the July 21 announcement of the company moving its headquarters to the cloud.

“Historically, the largest number of great technology companies emerged from Silicon Valley for good reason – the network effect. Many things drove the network effect, but the most important was this: if you were a great technology entrepreneur born anywhere in the world where it was difficult to start a company — such as Bangladesh or Sudan, or Marianna, Arkansas — and you decided to move, the place you were most likely to move to was Silicon Valley. As a result, Silicon Valley became the place that attracted most of the great national and international talent.”

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, companies realised that working remotely “is not perfect, but mitigating the cultural issues associated with remote work turns out to be easier than mitigating the employee satisfaction issues associated with forcing everyone into the office five days a week. As a result, nearly every technology company has moved to a remote or hybrid approach to work, and this change is profoundly weakening the Silicon Valley network effect.”

Financial firms have also taken bold steps to redistribute their workforce. Many have fallen for Miami’s tropical appeal, combined with the city’s low taxes, and tremendous economic and cultural renaissance — most notably $51bn hedge fund Citadel, which moved its headquarters from Chicago to Miami after members of its team first relocated to a local hotel during the early months of the pandemic as the trading floors in New York and Chicago were shut down because of the pandemic.

“At this particular moment in time, people are looking at Miami not only as a good place to visit, but also as a place where they can do ambitious things, launch new companies or relocate their companies. This traces back to our efforts around talent development,” says Matt Haggman, executive vice president of Opportunity Miami, an organisation powered by the Miami-Dade Beacon Council and working to secure the city’s long-term economic future.

Others have looked at Dallas. Goldman Sachs, for example, announced plans to develop a $500m, 5000-person hub in the city, although the company seems to be on a collision course with the local legislature over abortion rights in the wake of the Supreme court decision to overturn the Roe v Wade decision in June – the company has offered to cover travel costs for those employees that need to go out-of-state to receive abortion or gender-affirming medical care starting July 1, Reuters reported.

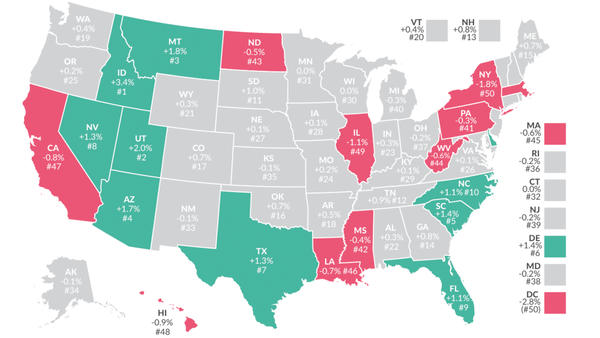

The new reality of the US job market is mirrored in the country’s latest figures on population change. In 2021, population losses were recorded in states that have traditionally been the country’s main business hubs, like New York, where the population fell by 1.8% in 2021 from a year earlier, Illinois (–1.1%) and California (–0.8%). The likes of Utah (+2%), Nevada (+1.3%), Texas (+1.7%) and Florida (+1.1%) featured among the states whose population increased the most in 2021.

Making it anywhere

Beyond corporate plans and figures, real change is already tangible on the ground, with investment and business activity popping up in places other than the usual suspects that have traditionally dominated the US job market.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, “maybe 25% had some element of remote work”, says Darcy Howe, referring to the start-ups in her VC firm’s portfolio. “Now I would say it is 90%.”

Ms Howe is the founder and managing director of KCRise Fund, a VC firm that was established in 2016 to support the start-up ecosystem of Kansas City, Missouri. She has seen first-hand how the rise of remote work has energised the city’s start-up community.

“I’m already seeing that more entrepreneurs are having the guts to start a company in Kansas City,” she says. “Because they realise, I can do it here, I don’t have to go somewhere else.”

While 68% of VC in 2021 was invested in the states of California, New York and Massachusetts, cities across the US are betting that the rise of remote work will drive tech talent and investment away from the coasts.

“The big superstar places are not going anywhere, but there’s a modest shift outwards into new areas,” says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies the shifting geography of tech talent. “They are clearly a new, emerging centre of action right now.”

The rise of the rest

The earliest investor to bet on this shift was Steve Case, the former CEO of AOL. After working with the Obama administration to promote high-growth entrepreneurship, he and his investment firm Revolution LLC criss-crossed the US by bus, visiting 44 cities to invest in local start-ups.

According to Mr Case, remote work has strengthened two key ingredients of emerging start-up ecosystems: talent and investment.

“Arguably the most important part of building a vibrant start-up community is winning the battle for talent,” Mr Case tells fDi. With tech workers relocating to their hometowns, “some will then leave their big companies to work for small companies or start their own companies. That dynamic will likely accelerate over the next few years.”

And those who start their own companies will have easier access to capital: “The pandemic has been this accelerant because suddenly people didn’t have to get on a plane to fly to Palo Alto to pitch on Sand Hill Road. They could do it by Zoom. And that led to more pitch meetings, which led to more investments.”

Remote work also lets start-ups in smaller cities hire across the country. While Kansas City has limited talent, explains Ms Howe, “we’re very much in the broader ecosystem of talent for venture-backed companies, and that has really helped us a lot.”

Catching the boomerangs

As tech workers leave tech hubs, a key priority for economic development leaders has been to attract the aforementioned boomerangs.

For Joe O’Connor, a Kansas-City-native who returned from San Francisco during the pandemic, remote work made the decision to move home a lot easier.

“I did think I would have eventually come back to Kansas City,” he says, citing proximity to family and a lower cost of living. But he also wanted to join the founding team of a start-up. He had his chance to do so at Chisel, a San Francisco-based start-up that makes product management software. Remote work allowed him to move home and join the start-up.

“Chisel is a remote-first company. Our headquarters are out of the Bay Area, but we have people in Boston, New Jersey, Los Angeles and Kansas City, and our engineering team is in India. So, we’re all over the place.”

Economic development challenge

The flipside of attracting remote workers and a talent-centric approach of economic development is the risk that companies will never set up a local physical presence.

“Companies have learnt during the pandemic they can manage a globally dispersed global workforce,” Andreas Dressler, managing director at Berlin-based consultancy FDI Center, tells fDi. “An increasing number of companies will just hire talent anywhere. If a city promotes itself as a talent base, they will take note and hire talent remotely, without investing directly in the specific place where that talent is sourced.

“Companies are already approaching IPAs and EDOs enquiring about local talent. They are hiring people locally, but [don’t set up a local office or have a local] physical presence. Is that a positive?”

The EIG has tried to answer that question by looking into the local economic impact of the Tulsa Remote programme. Although it highlighted the challenges of capturing the full impact of remote workers on the local economy, “given the non-traditional nature of their work”, the EIG estimated that the 450 remote workers that became members of the initiative before the start of 2021 contributed to $62m in new labour income — $51.3m in direct labour income from remote workers and $10.7m in induced local labour income. In other words, each dollar invested by Tulsa Remote returned $13.77.

In terms of tax revenues, each programme member induced enough economic activity to create $4000 in new state and local tax revenue, the EIG has estimated.

Looking forward, and based on growth projections supplied by Tulsa Remote, the combined new employment in Tulsa as a result of the programme is projected to be upwards of 5000 people in 2025, including at least 1500 induced jobs, the EIG estimates. The new labour income in the local economy in 2025 alone is projected to range from $485.4m to $518.2m.

Elon’s ultimatum

As Covid restrictions fall across the geographies — except for a few exceptions, including China — people and companies are once again reassessing their work arrangements. In the US alone, the share of employed persons working from home peaked at 30.4% in May 2020, only to fall back to 13.2% in July 2021, according to figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

High-profile members of the tech community have cooled off on the prospects of remote work arrangements.

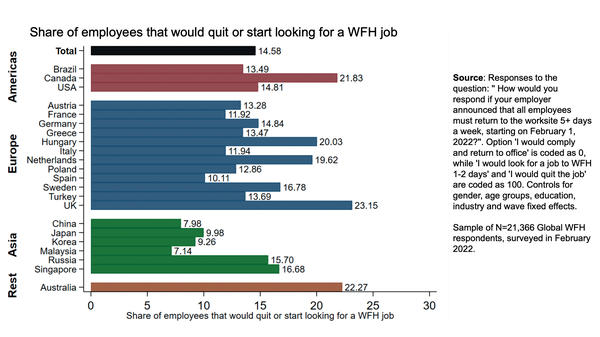

In late May, the entrepreneur Elon Musk declared that “remote work is no longer acceptable” at Tesla, encouraging his employees to come back to the office. As the urgency of the Covid-19 pandemic fades and tech layoffs rise, the staying power of remote work is far from clear.

Mr Muro cautions that the data on tech workers does not always align with the popular narrative: “Big tech exiting from the coasts has been a bit oversold. There has been an exiting, but the bulk of it is to adjacent counties or within the state,” not across the country.

The long-term shifts in tech talent, he thinks, can be divided into three categories: the “rising star” cities driven by corporations seeking cheaper but still established labour markets, smaller cities with dynamic universities, and “lifestyle places” that attract truly remote workers to their natural beauty or unique amenities.

As recession fears rattle technology markets, Mr Muro suspects the appeal of “lifestyle places” may fade. “We are going to have a little less frothy markets for the next couple of years,” he predicts. “My gut [feeling] is that might make companies and people more conservative.”

The aforementioned Mr Case, on the other hand, is optimistic about the prospect of executives like Mr Musk calling their workers back to San Francisco and New York, predicting that tech workers who left will refuse to go back.

“If my first choice is to work remotely and you tell me that’s no longer an option, I’m going to leave your company and work for somebody here,” he suggests. “And that actually will likely have an accelerating impact for the start-ups in those different cities.”

Economic development and investment promotion will adjust accordingly, although the focus on talent seems destined to stay. Policy-makers at the national level have bought into this paradigm shift too, with 44 countries offering special visas to remote and skilled workers as of July 21, according to digital nomad online hub nomadgirl.co.

“Competition for FDI is turning into competition for talent,” Chris Knight, co-founder of investment consultancy Wavteq, tells fDi. “Should governments incentivise companies to set up, or people to relocate? Companies will follow the talent, and I think that over the years EDOs and IPAs will go to less trade shows and more university fairs.”

This article first appeared in the August/September 2022 print edition of fDi Intelligence.